Center Market's Chaotic Exuberance

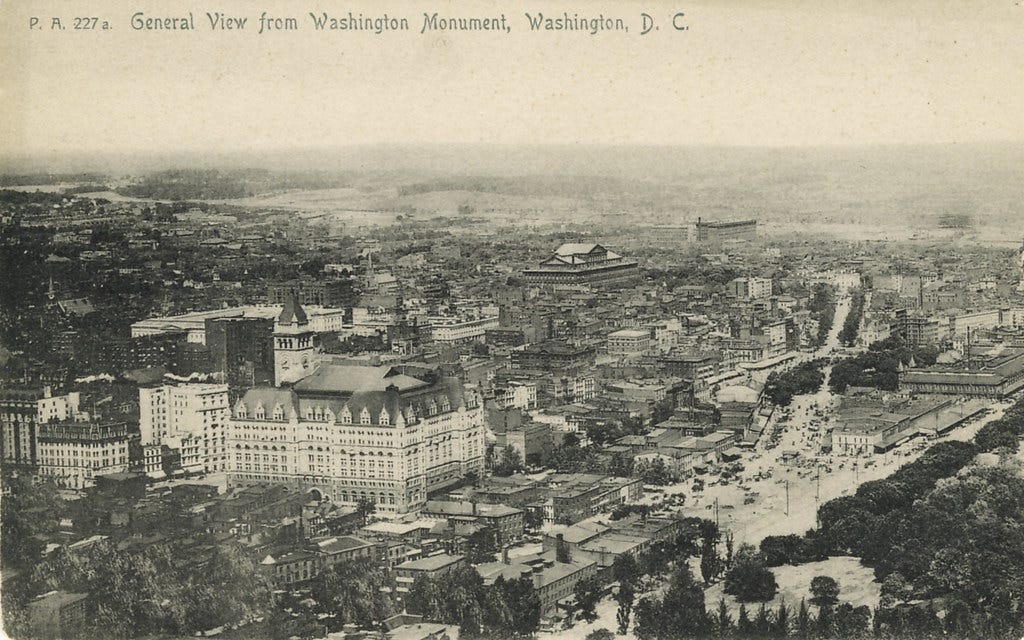

Before the buttoned-down, neoclassical National Archives building came to dominate the intersection of Seventh Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, an entirely different architectural and cultural landscape was present for more than a hundred years: a massive, sprawling marketplace, one of the biggest in the country.

This was once perhaps the most central spot in the city, half way between the White House and the Capitol on Pennsylvania Avenue and intersecting one of the few roads (Seventh Street) that led out of the city to parts north. George Washington himself designated this spot as a marketplace, and the first Center Market opened for business here in 1801 in a building designed in part by James Hoban, architect of the White House. Additional markets (including Western Market, Eastern Market, Northern Liberty Market, and others) would be established as well, but Center Market was always the biggest and busiest.

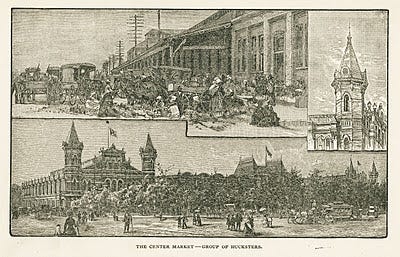

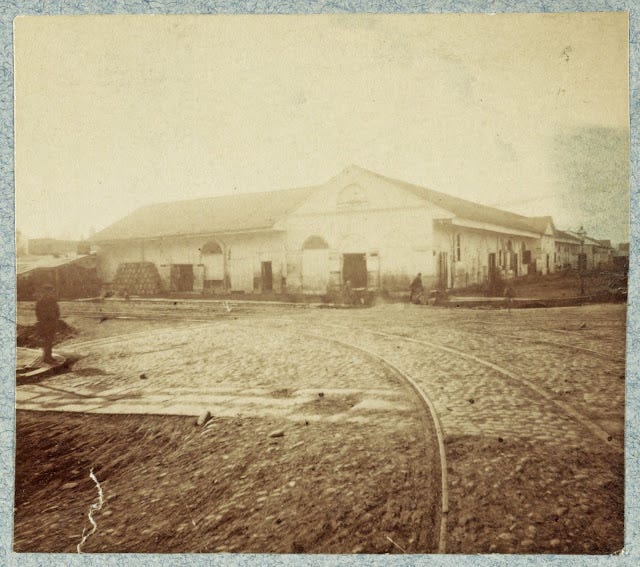

In its earliest days it was aptly known as the Marsh Market; Tiber Creek originally ran through part of the market's square, and fish vendors would store live fish in wire baskets that they lowered into the creek. A major effort was undertaken in 1823 to level and raise the ground and confine the creek to the Washington Canal bed along B Street (Constitution Avenue). Despite the reclaimed terra firma, the Marsh Market was crowded and chaotic on market days; farmers from all parts congregated with their wagons, horses, livestock, and produce; customers jockeyed for the best buys; and other assorted hucksters and hangers-on found ways to feed off the activity. The marshy areas in the vicinity of the canal and market supported numerous waterfowl, and boys would happily find and shoot them and then immediately sell them to vendors in the marketplace.

By the 1850s, Center Market was an unsightly, unsanitary, and overgrown sprawl of assorted buildings and shacks that encroached on the streets around it and still could barely contain all the market activity it supported. In a paper delivered before the Columbia Historical Society (now the DC History Center) in 1922, hat-merchant-turned-amateur-historian Washington Topham recalled the old market:

As a boy I used to go in and out of the old Centre Market, before the present splendid structures were built, and I well remember their quaint appearance, the old wooden sheds, the low, soiled, whitewashed, weather-beaten walls, with the green moss growing over the shingled roof and hanging from the eaves.

Efforts were undertaken to plan a modern replacement for the old structures, but the Civil War intervened and postponed any action. In those days, a market such as this was a staple fixture of any large metropolitan area; local governments generally set them up in central locations and enacted regulations to encourage their use so as to ensure that citizens of all means could have access to a broad range of affordable food. In the case of Center Market, the property was owned and operated by the federal government, although an 1860 law turned it over to the D.C. government, provided that a new building was constructed within two years, which didn't happen. There followed considerable wrangling between obstinate individuals, both in Congress and the city government, over how a new market house should be funded and built. Finally in 1870 Congress passed a law incorporating a private Washington Market Company to raise funds through the sale of stock to build the new market house. Company sponsors promised that "instead of the loathsome pile of rubbish" that constituted the existing market, they would build "a stately and elegant structure" with "magnificent entrances and porches to the edifices."

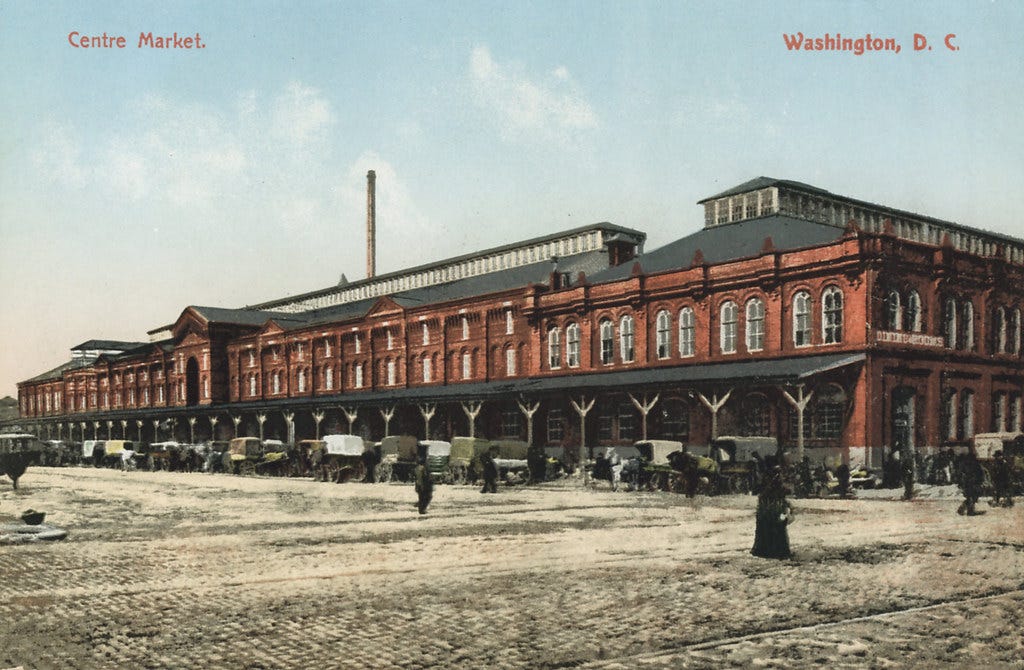

Closely connected to both the D.C. government and the new market company was architect Adolf Cluss who designed many prominent Washington buildings in the days when pressed red brick was king, including Shepherd's Row, the old Masonic Temple, the original National Museum building, the Calvary Baptist Church, and many others. For the new Center Market Cluss designed an elaborate square of four connected buildings with an open courtyard in the center. The design seemed to reach a compromise between the stateliness requisite of a grand Pennsylvania Avenue building and the Victorian eccentricities that were the fashion of the day. As with several of his other buildings, Cluss incorporated elements of the German Renaissance Revival into the structure's extensive decorations, which also included multiple stringcourses and fanciful towers. The rear and two side buildings containing the market wings and their twin-towered facades were completed and opened on time in 1872, but the central building on the north side was not finished until several years later.

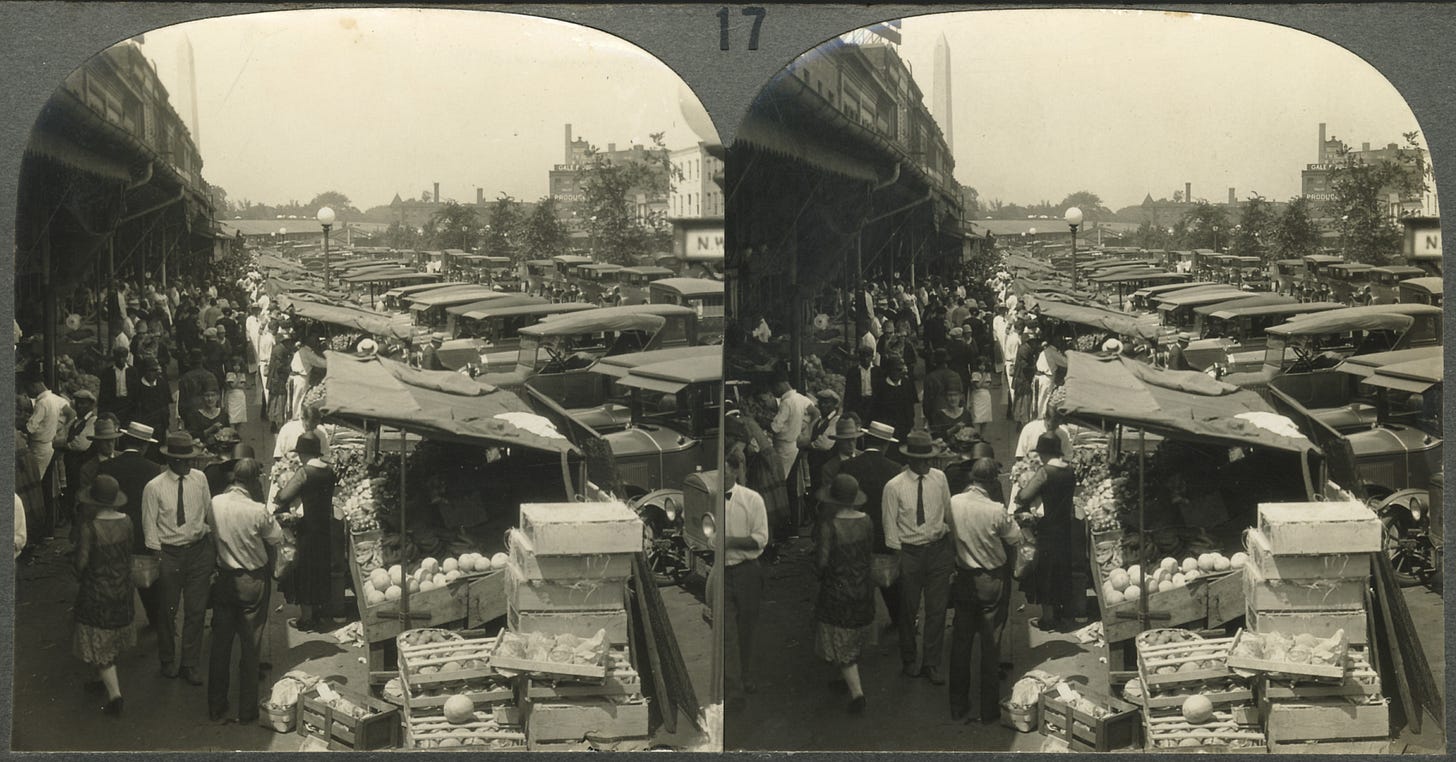

At 57,500 square feet and 666 separate vendor stalls, Cluss claimed in 1878 that the market was the largest in the country. It was designed to incorporate the most advanced ideas of the time, including two-story-high corridors to allow for plenty of ventilation, eight electric elevators, the city's first cold-storage vaults, its own artesian wells, and an ice plant. While established merchants could rent out one or more stalls in the market itself, others with fewer resources could rent space in the courtyard and sell from their own makeshift stands.

One successful merchant was Louis P. Gatti, an Italian immigrant who operated a fruit and vegetable stand at Center Market from about 1900 to 1925. At his death in 1969, the Washington Post noted that Gatti's fruit and vegetable stand “won the culinary cachet of early 20th century Washington….[T]he fine quality of his fruits and vegetables—such as strawberries from Plant City, Fla., and typhoid-free watercress grown in pure mineral springs—won him an elite clientele of the rich and powerful in a day when even the most haughty of the city’s housewives did their own daily grocery shopping.” A 1948 article further elaborates: “Numbered among their clients were Presidents Taft, Wilson, and Harding, Cabinet officials, diplomats, and official leaders of the day….Mrs. Gatti often reminisced about the time Mrs. William Howard Taft came to her after the President’s inauguration, asking if she would take as good care of the White House larder as she had the Taft residence.”

Of course, not everyone was as successful as Gatti. The handsome market building designed by Cluss ended up being as overrun as its predecessors with every sort of huckster vying for some small piece of the action. A Post article from 1887 reported the complaints of farmers, truckers, and "fruit raisers" who rented space behind the market on B Street where they sold produce directly to customers from their wagons. They complained about unlicensed competitors who "not only sell to our detriment but take possession of the space allowed us for our wagons, so that daily we are obliged to stand in the middle of the street." To add injury to insult, these farmers were also required to pay five or ten cents a day to market policemen, ostensibly to cover the costs of sweeping the sidewalks, whereas everybody knew that the policemen were merely pocketing the money. -It just wasn't easy trying to make a living as a small-time farmer.

In July 1896, a dozen Greek immigrants were arrested for blocking access to the market with their pushcarts. "Notwithstanding the fines repeatedly imposed upon these vendors, they will insist upon crowding beyond the lines prescribed by the police regulations," the Post commented. "They paid no heed to the warning of the police, and would no sooner be driven back on their stand than they were out in the street again." A subsequent notice in October of the same year found the group arrested again for the same violation.

Of note were a wide variety of African Americans selling all manner of foodstuffs in what was likely the only venue available to them at that time—the market curbside, which they could occupy for free as long as they claimed their space before anyone else. In 1892, under the title, "War Didn't Efface Them," the Post reported on older African Americans that had survived slavery: "Here on every market day year in and year out are to be found the sturdy remnants of the old plantation stock. Nearly all of them own their own little patch of ground, and their stock in trade displayed on an upturned box or barrel consists of what they can raise with the hoe or glean from the wild products of the woods and fields." Among the products on sale were "the first bunches of half-opened arbutus and dog-toothed violets" in early summer, along with "green leeks and little white spring onions and little indigestible bunches of red and white radishes... Later in the season the stands along the south wall bloom out with a wealth of color, golden rod and crimson dahlias with stiff-leafed zenias and cockscomb and bachelor's button, the latter warranted to keep indefinitely." One could also observe live terrapins "tethered by one leg to one of the rusty nails that protrude from the edge of the soap box which serves the terrapin's owner for a seat."

A Washington Times reporter recorded her own interactions at curbside in 1902: "What in the world is this? she asked. "That's a mud turtle's flipper, caught in the full of the moon." "Is it 5 cents?" "Lord, no. Flippers come high, lady--when they're caught in the full of the moon. That identical flipper is worth all of 15 cents, but you can have it this morning for 10." "And how much for the hare's foot?" "That's a first-class hare's foot, lady. I ain't seen none to beat it nowhere—but I ain't going to tote it back home if you want it bad enough to pay a dime. There ain't no luck to beat a hare's foot—excepting turtle flippers, of course."

After World War I, substantial changes in the food industry began to spell doom for municipal markets like Center Market. Processed foods such as canned and frozen foods, the invention of ever-more-sophisticated food storage and display fixtures, and the rise of local community markets meant that people increasingly no longer needed to come down to the old central marketplace to shop. With the tremendous growth of the city, such a market was increasingly inconvenient. Perhaps most importantly, the grimy, sprawling, red-brick Victorian pile was incompatible with the McMillan Commission's vision of a pristine, monumental, white-marble city core.

The market had returned to federal government control in 1921, when a new law was passed revoking the charter of the Washington Market Company and paving the way for the market's eventual removal. Needless to say, merchants put up a long and hard-fought battle to save it, arguing that George Washington himself had reserved the site for use as a market and thus it had to stay. In the end, the Supreme Court upheld a ruling that the government had legal title to the land and could use it any way it saw fit. Center Market closed its doors for good on January 1, 1931, and was razed over the next several months. A five-foot marble slab, inscribed with the history of the market, was saved from the building's northwest wall, but, like many such artifacts, its current location is unknown. Over one hundred merchants chose to move to the Northern Liberty Market at 5th and K Streets, NW, which took on the Center Market moniker for several decades. Other merchants moved to the Western, Arcade, Park View, or Riggs markets, or simply went out of business altogether. The National Archives building was completed on the site in 1937.