The Farragut Statue: Vinnie Ream's "Other" Big Commission

In 1872, Congress appropriated $20,000 "for the purpose of erecting a colossal statue of Admiral David G. Farragut...in Farragut Square in the City of Washington." Farragut, who had just died in 1870, was one of the great naval heroes of the Civil War, famous for his supposed cry of "Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead" at the Battle of Mobile Bay. Thus the obvious need for a colossal statue of the man. -But who should sculpt this statue? Twenty-four sculptors would officially compete for the honor, but it seems the Admiral's widow, along with General William Tecumseh Sherman, head of the selection committee, knew who they wanted. It was Vinnie Ream, the "radiant-faced, dark-eyed little woman" (as described in the Washington Post) who had sculpted Abraham Lincoln for the Capitol Rotunda.

Born Lavinia Ellen Ream in Madison, Wisconsin, in 1847, Ms. Ream moved around quite a bit as a child due to the demands of her father's job as a government surveyor. The family had been in Washington for a time but then were back "out west" when she attended Christian College in Columbia, Missouri, where she developed her talents in music and poetry. She was introduced as one of the school's star pupils to Missouri politician James S. Rollins, who would join the U.S. House of Representatives in 1861, the same year that Ream's family moved permanently to Washington. It was on the basis of Rollins' connections that Ream got herself established as an assistant in the workshop of Clark Mills, the most prominent Washington sculptor of the day. Mills had done the statues of Jackson in Lafayette Square and Washington in Washington Circle.

There's a long story of how Ream then came to be commissioned in 1866—when she was only 18—to create a commemorative statue of Lincoln to be placed in the rotunda of the Capitol. This was the first government sculpture commission ever received by a woman, and it was not without controversy. Ream had already demonstrated her ability to capitalize on personal connections, and she developed many more as she met the Washington power brokers who visited Mills' studio. Rather than having a standard competition held, with entries judged by an independent panel, Ream's supporters on Capitol Hill crafted a bill that would directly confer the Lincoln commission on her. When a few Eastern senators, including Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, questioned whether Ream was qualified for the task, her supporters championed her as the "this young scion from the West, from the same land which Lincoln came from—a young person who manifests intuitive genius..." The bill passed; Ream got her commission.

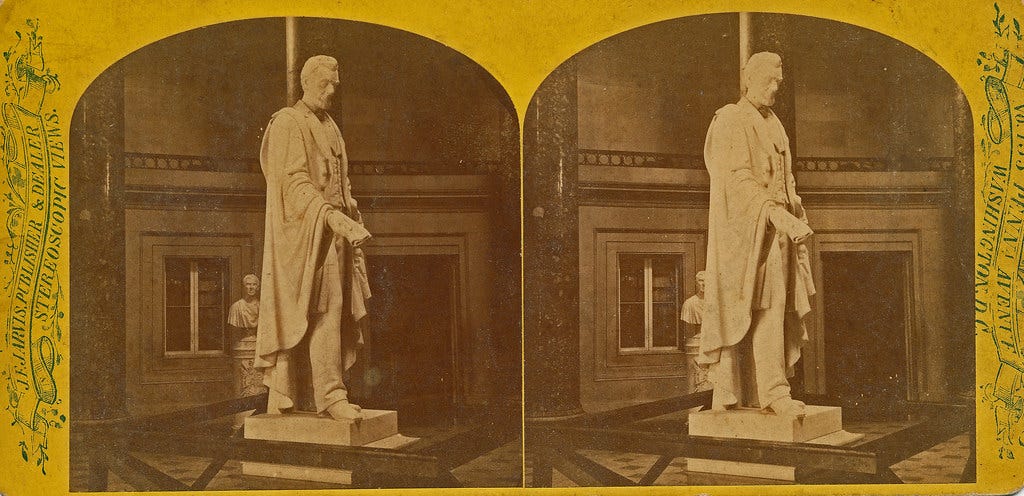

Ream had made a clay bust of Lincoln in Mills' studio that helped influence the decision. She would tell stories of how she had pursued the opportunity to go to the White House and model this bust from life, that Lincoln had initially refused but then relented upon hearing that she was "poor," allowing her to observe him at his desk for a half an hour per day over several months. She saw an occasional tear roll down his cheek at the thought of his dead son Willie, etc., etc. Unfortunately, there is no evidence to corroborate that she was ever actually at the White House. Further, when she wrote Mary Todd Lincoln requesting an endorsement, Mrs. Lincoln responded forcefully to the effect that she was unaware of Ream ever visiting Mr. Lincoln and was quite sure it had never happened. Regardless, Ream went on to model the statue of Lincoln, have it carved from Carrara marble in Italy (because it was cheaper than having it done in the U.S.), and saw it erected with much fanfare in the Capitol Rotunda in 1871. Critical opinion of the statue was divided. If you look closely at the face of the statue, it has a rather somnolent gaze. Some think Ream modeled it from a life mask of Lincoln made by Clark Mills in February 1865.

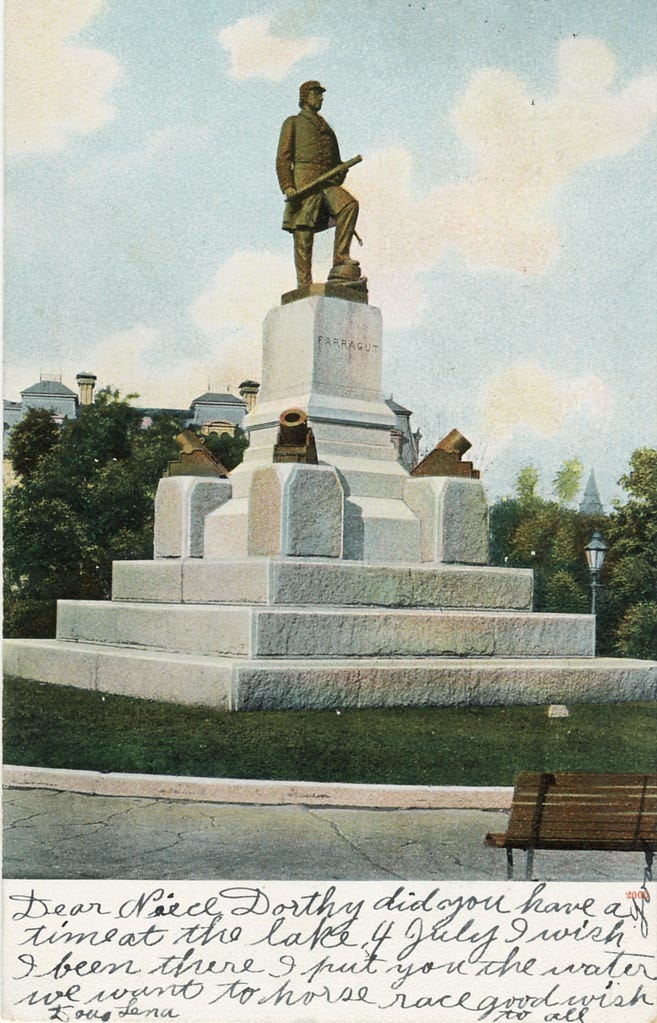

It was essentially on the heels of her great success with the Lincoln statue that Ream jumped on the opportunity to do the Farragut statue the following year. Again she faced stiff competition from more accomplished sculptors, and again she energetically worked her supporters on Capitol Hill to ensure she got the commission. Working from photographs of the admiral given to her by Mrs. Farragut, Ream took three years to complete a seven-foot plaster cast model of the statue. She then spent another seven years at a special studio set up for her at the Washington Navy Yard, working on casting the final ten-foot bronze statue from the propellers of the Admiral's flagship, the U.S.S. Hartford. It was during this time that Ream met, through Mrs. Farragut, Lieutenant Richard L. Hoxie of the Army Corps of Engineers, whom she married in 1878. As Mrs. Vinnie Ream Hoxie, she participated in the lavish dedication ceremony for her statue in April 1881. Assorted military units marched the traditional route up Pennsylvania Avenue and around to Farragut Square, where President Garfield made his first public address since being inaugurated. Crowds were massive, government workers having been given time off to attend the event. Ream and Mrs. Farragut shared honors with the President on the dedication stand. After all the excitement was over, Mrs. Hoxie could still see her creation every day; the Hoxies had moved into 1632 K Street, NW, which had a view on to Farragut Square.

Vinnie Ream Hoxie was a minor celebrity by this point, although she produced little other sculpture. An article in the Washington Post in 1900 noted that "The heroic bronze of Farragut...was the last work for which the sculptor received compensation, Maj. Hoxie, with a chivalrous manliness, preferring that his wife should be altogether dependent upon himself." We think he was indeed chivalrous--for providing Vinnie with such a convenient cover.

What, then, can we say about the "heroic" statue of Admiral Farragut and Vinnie Ream's accomplishments in general? Horace Greeley, never one to mince words, once reportedly called Ream "one of the most audacious little humbugs of the age...[a] phenomenon of successful impudence such as no country but America ever did or could produce." This seems a little overly passionate. At a minimum, one has to admire the woman's gumption. And the Farragut statue, if not a great work of art, certainly gets done the job it was supposed to do. What do you think?