The Little Shop That Survived

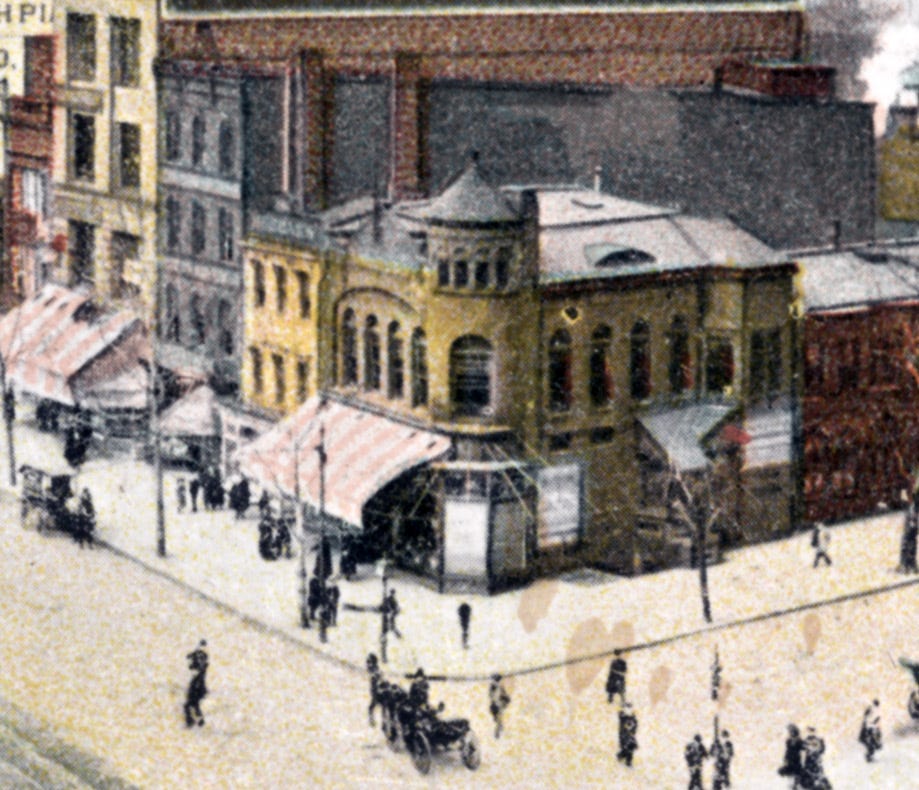

A recent article in The Washington Post about the historic synagogue downtown that was moved once and will be moved again soon got me thinking about historic buildings in D.C. that have been moved. Georgetown's exquisite Dumbarton House is another example; it was moved north about 50 feet in 1915 to allow the Georgetown stretch of Q Street to be connected up with its Washington counterpart. A much humbler structure that's been dismantled and its facade partially rebuilt several blocks away is the little commercial storefront that used to sit on the northwest corner of 12th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, visible in this postcard from about 1910.

The charming little building, erected in 1886, has a bit of eclectic architectural flair—some interesting Romanesque Revival touches, such as are more often seen on larger structures. It's likely that little of this building's history is known, despite its prominent location on a busy corner opposite the Raleigh Hotel and across from the Old Post Office building, where the source photograph for this view was taken.

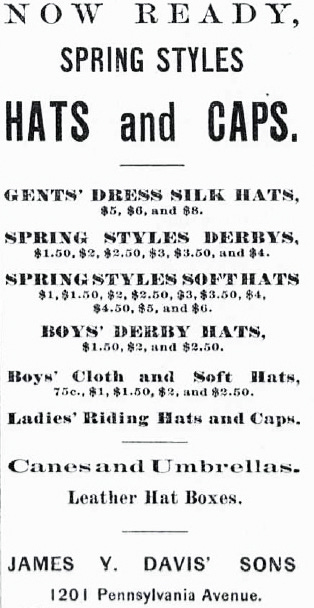

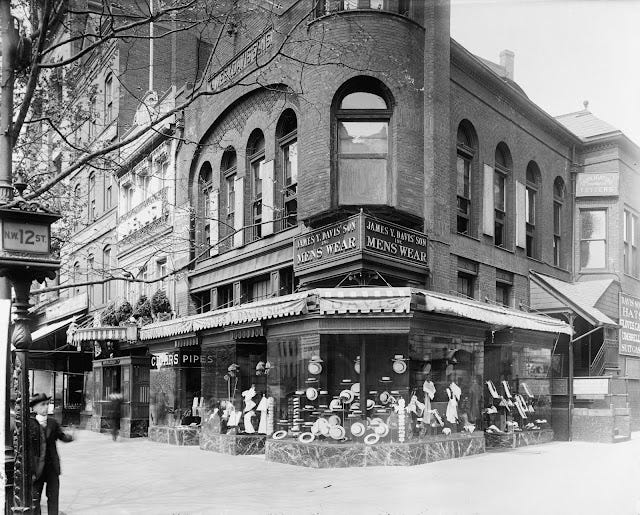

A hat store operated by James Y. Davis' Sons was our building's first occupant on the ground floor. The Davis hat firm had been in operation at other locations since 1830, making it one of the oldest in the city. On the second floor a jeweler by the name of Joseph Drukker set up shop. Drukker's upstairs business must not have done too well. In January 1903, he declared bankruptcy, his debt of $6,095.72 apparently being insurmountable with assets of only approximately $3,700.

The James Y. Davis Store, c. 1919. Source: Library of Congress.

Closeup of the James Y. Davis Store, c. 1911. (Source: Library of Congress)

The building had many other tenants through the years, including the United Cigar Stores, an Arthur Murray Dance Studio, the Raleigh Gift Shop, and Samuel Saidman Men's Furnishings. In 1922 it became the first home of Ciro Gallotti's Italian-American Restaurant, which would do a brisk business there for almost 20 years. But time eventually caught up with the little storefront. As we all know, downtown hit a particularly bleak stretch in the 1960s and 1970s. By then, Washington Wine and Liquors was on the ground floor and the upper floor was vacant. The Avenue in those days was lined with a scattered and largely unsightly potpourri of randomly-surviving buildings of differing scales and quality, punctuated by parking lots.

The building as documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey in the 1970s (Source: Library of Congress).

1201 Pennsylvania Avenue NW shortly before being disassembled in 1979 (Source: Archives of the D.C. Preservation League).

President Kennedy famously had wanted "America's Main Street" to be more dignified and stately. After various commissions and studies weighed in, Congress set up the Pennsylvania Avenue Development Corporation in 1972, and it submitted its plan for redeveloping the Avenue two years later. The plan addressed historic preservation where the corporation found it feasible; thus, some old buildings were saved, others not. The corporation had been charged with the "preservation and rehabilitation of important structures that contribute to the Avenue's ceremonial, physical, and historic character," as asserted in its 1979 annual report. Accordingly, the corporation encouraged restoration of the Central National Bank building at 7th Street, the Fireman's Insurance Company at 7th and Indiana Avenue, and the Jenifer Building at 7th and E. It also ensured that the Evening Star Building and the Hotel Washington were preserved as well as the great Willard Hotel at 14th Street. But other historically significant buildings got little love from the PADC. The Munsey Building, for example, where the J.W. Marriott Hotel is now located, was sacrificed, perhaps because officials were afraid of saddling developers with the expense of preserving it.

Likewise, Kann's Department Store, which was actually a collection of 15 structures built between 1885 and 1900 that had been grouped under a single modernist facade in the 1960s, also met an ignominious end. The company went out of business in 1975, and the PADC acquired its building with the intent of demolishing it so that a new "superblock" multi-use housing complex could be constructed. Preservationists succeeded in delaying demolition of the old structure for a time as they struggled to find ways to save it, including through a developer's proposal to incorporate the facades of the old buildings into a new housing complex. As the struggle went on, however, the abandoned building caught fire dramatically in April 1979, destroying much of its interior. The PADC then razed the remains of the structure, saving nothing.

The Kann's fire, April 1979 (Source: Archives of the D.C. Preservation League)

In contrast, the little storefront on the corner of 12th and Pennsylvania met no such dramatic end and was not completely annihilated. Instead it was marked for semi-preservation, as it were. It was carefully taken down in June 1979, and pieces of its facade were numbered and put into storage. The PADC didn't have a specific plan for what it would do with these pieces, but they would be available for reuse somewhere else. Construction then began at 12th and Pennsylvania on the $30 million Heurich Building, designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, which was completed in 1981 and now fills much of the block. The deep setback of the new building means that the old storefront's spot is actually now part of the sidewalk.

Construction at 12th and Pennsylvania, 1979 (Source: Archives of the D.C. Preservation League)

12th and Pennsylvania NW as seen today from the Old Post Office Tower.

Meanwhile, the pieces of the store's facade languished in storage for more than a decade. Then, in one of its last acts before being dissolved by Congress in 1996, the PADC worked with Pepco to use the stored facade elements, along with those of several other buildings torn down in the PADC's realm, to mask the blank wall of the electrical substation on 8th Street.

In his review of this pastiche of building parts, Benjamin Forgey observed that "as a serious strategy for historic preservation the wall is negligible—a mere curiosity," but also noted the irony of their appearance here "flattened like a butterfly in a book" when they were supposed to have been reused as elements of new buildings. This turned out to be an unrealistic expectation. PADC officials tried repeatedly to have new development incorporate the facade elements, but developers resisted and financing proved elusive. Finally, the staff came up with the Pepco substation use when all else failed. The row of ghost-like building shards is certainly a better outcome than if all this material had been completely lost. On the other hand, it is also a perennial reminder of how hard it is to find ways to integrate our historic heritage with our aspirations for the future.

1201 Pennsylvania Avenue's current home on 8th Street NW

[Ed. note: I made revisions to this article in response to new information graciously provided by a former PADC staffer. I appreciate the assistance.]