The Munsey Building (1905-1980) Remembered

Frank Munsey was a Gilded Age capitalist—robber baron, if you will—who had a major influence on the publishing business at the beginning of the twentieth century. He is credited with perfecting printing processes that could use extremely low-quality “pulp” paper to produce periodicals that were both dirt-cheap and filled with enough racy fare to be widely popular. Thus was born the era of pulp fiction. Munsey went on to buy, sell, and merge many newspapers throughout the country, often for his own profit but at the expense of the publication’s very existence.

One of Munsey’s newspaper acquisitions was the Washington Times, founded by a group of Washington printers in 1894 and acquired by Munsey in 1901 (note: there is no connection between the original Times and the current newspaper of the same name, which began in the 1980s). In 1905, Munsey built a grand new skyscraper of an office building at 1329 E Street, N.W., to house his newspaper. The structures on this block essentially faced Pennsylvania Avenue at the time. The new Munsey Building was just a few doors down from the Richardson-Romanesque Washington Post building and a couple of blocks west of the Evening Star building, so all the important journalists of the early 1900s were in close proximity along this stretch of the Avenue.

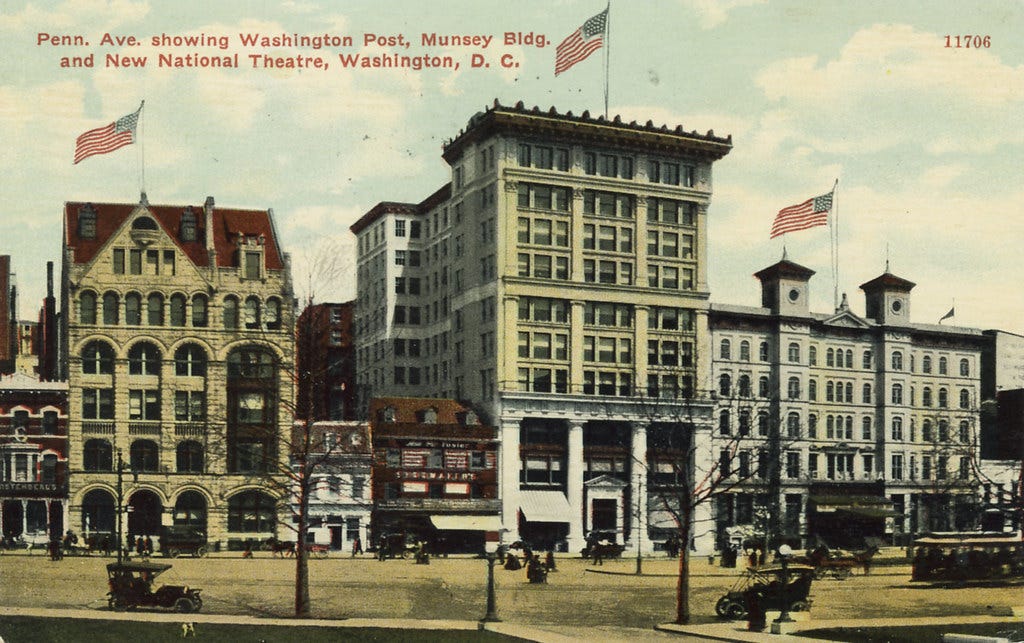

As seen in this postcard, the original building of 1905 (the tall building with the elaborate cornice) had a fairly ornate façade, which was redone and simplified sometime between 1910 and 1915. (The Historic American Buildings Survey description of the Munsey building, compiled in 1979, states that only one image was extant at that time of the building in its original configuration, but these postcards, from about 1908, also show the original configuration.) In 1915, an addition was built that more-or-less doubled the size of the building, extending it all the way to the gable-roofed Washington Post building on the left.

The Munsey Building was unquestionably meant to be a prestige office building, and Munsey spared no expense in attaining that goal. He hired the premiere architectural firm, McKim, Mead, and White of New York City, to design the elegant 12-storey Italian Renaissance Revival building and used high-quality materials throughout. The interior banking room on the first floor had marble paneled walls punctuated by marble Roman Doric pilasters and had luxurious marble, wood, and brass detailing. The upper corridors had black and red marble bands in the floor design marking the entrances to offices. Even the restrooms had marble wainscoting. When selling the building to his own banking company in 1913, Munsey published an editorial defending his investment in the building: “The Munsey Building was built by the Fuller Company, and at a cost of close to sixty cents a cubic foot—sixty cents, mind you, against thirty or thirty-five cents, the cost per cubic foot of putting up fairly good office buildings, but not buildings of real class or genuine in quality.”

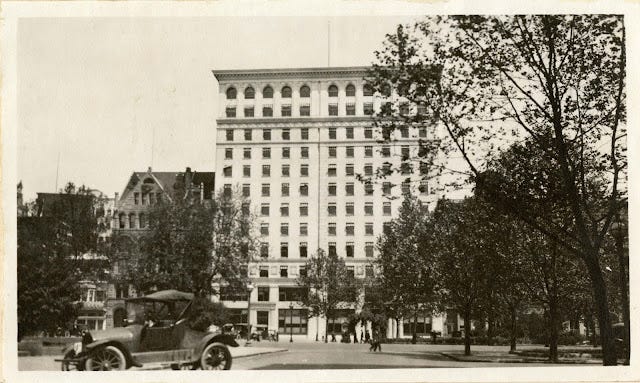

The Munsey Building in 1919, after it was nearly doubled in size. (Source: Smithsonian Archives via Flickr)

The culprit in our story is the Pennsylvania Avenue Development Corporation (PADC), chartered by Congress in 1972 to redevelop the area around Pennsylvania Avenue between the Capitol and the White House. In its 1974 plan, the PADC essentially damned the entire block where the Munsey stood with the statement that “(t)here are few structures of landmark quality in this square.” The Munsey Building itself was dismissed as a “well-defined, early 20th Century commercial building” that was “somewhat outdated by competitive standards.” In 1979, the PADC bought the then-vacant building with the intention of demolishing it so that a new hotel and office complex could be constructed. I took the following picture of the block in early 1980, when work was underway to build Freedom Plaza and the building was being prepared for demolition.

The Munsey Building in 1980 with netting on the east side in preparation for demolition. (Photo by the author.)

There was certainly opposition to the move. The courts temporarily blocked demolition while lawyers for Don’t Tear It Down, the predecessor of the D.C. Preservation League, tried desperately to save the Munsey. The PADC essentially argued that it had special status and powers to do anything consistently with its approved plan for Pennsylvania Avenue, and the courts ruled that its actions didn’t conflict with the Historic Preservation Act. The demolition proceeded.

I was there again in the fall of 1980, on a weekend when demolition was taking place and took these photos of the demolition and the spectators in Freedom Plaza who were transfixed by it.

It seems worth considering now, thirty years later, what, if anything, has changed, and whether this shocking and wanton destruction would take place again today in similar circumstances. Perhaps it’s those circumstances that are the key. In 1979, historic preservation and reuse downtown were not yet well-established, and many still worried about when or how downtown would be revitalized. Perhaps, then, it was just lack of faith—or imagination, or courage—on the part of the PADC as to what was the true potential of an historic structure like the Munsey. In hindsight, we probably can unanimously agree that a sensitive restoration and reuse of the Munsey would have been a far better amenity for Pennsylvania Avenue than the bland hotel building that sits there today.

The site as it looks today (photo by the author).