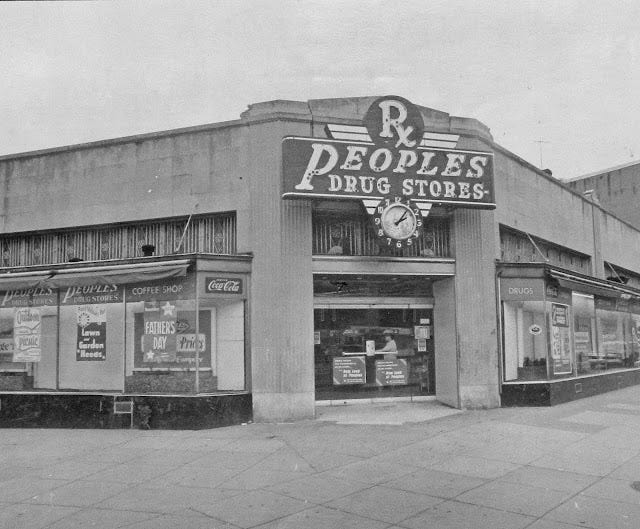

They used to be everywhere. Peoples Drug Stores were for much of the twentieth century one of those staples of everyday life in Washington, squatting on street corners in almost every neighborhood. The name seemed to have special resonance in the nation's capital, as if it were a commercial incarnation of democracy itself (or perhaps an arm of the Communist Party, depending on your perspective). It grew to be one of the largest drugstore chains on the east coast, with over 500 stores at one point ranging from Georgia to Ohio. And it all began here in the District.

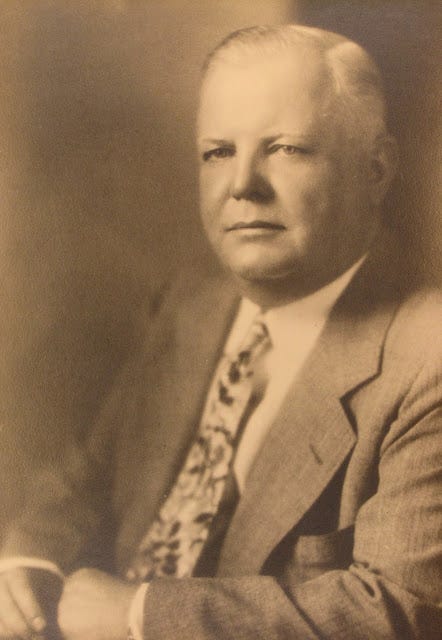

Peoples was founded in 1905 by Malcolm G. Gibbs (1877-1944), a native of Union City, Tennessee. Impatient with the limited opportunities in his small home town near the Mississippi river, Mac Gibbs decided in 1898 to join his brother, Campbell Gibbs, in Washington, D.C. As told by John V. Horner in a 1955 Evening Star article, Gibbs was a rather naive young man. He needed a porter to show him how to use his sleeper berth on the train to D.C., and when he arrived his first experience of the big city was to literally be taken for a ride. He gave a cab driver the address of his brother's rooming house and was driven around for a long time before finally arriving and being charged a full dollar. The next morning he discovered he was less than two blocks from the train station.

Of course, Gibbs soon gained his bearings. In Union City he had worked for the local newspaper, run by his father, so when he came to Washington he first sought employment at the Star. He was turned down. By one account he then got a job driving a laundry truck but wasn't happy with it. Eventually he responded to a help-wanted ad for a stockroom boy at Mertz's Modern Pharmacy at 11th and F Streets NW. Owner Edward P. Mertz (1861-1941) "noted the young man's frailty and also that he was lame. He doubted that Malcolm would be equal to the demands of the stockroom," according to Horner. But when Gibbs offered to prove his abilities by working for nothing at the start, he got the job and soon won over his boss. Like all those other success stories from 100 years ago, Gibbs worked hard, saved his money, and went to school at night, in time becoming a registered pharmacist. With $800 in 1905, he finally went into business for himself with a broker named Howard W. Silsby (who put in $8,000). They opened the first Peoples Drug Store at 824 7th Street, NW, just north of King's Palace.

It was a fortuitous time to be entering the retail pharmacy business. Small-time apothecaries focusing almost exclusively on prescriptions would soon become an endangered species. Energetic young entrepreneurs like Gibbs were transforming the business, offering a wider and wider variety of merchandise, advertising heavily, and offering discounted prices to lure in large numbers of customers. The formula had worked for the Woodward & Lothrop department store, and it would work for Peoples Drug as well.

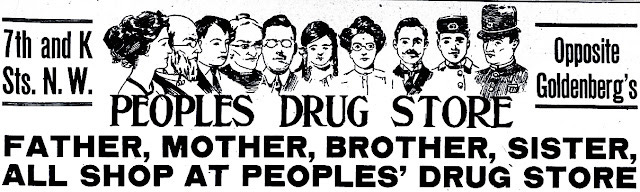

After four years, Peoples had outgrown its small storefront and moved to a spacious multi-storied building at the busy intersection of 7th and K Streets, NW, on the southeast corner of Mount Vernon Square. As described in The Washington Post, the new store was a marvel of retail innovation, a “department drug store, in which the stock ranges from the simplest drug compounds to teas, coffees, and rarest of perfumes.” Finished in gold and white with many mirrored surfaces, the first floor featured drugs and “drug sundries,” including the prescription counter, as well as an elaborate soda fountain and cigar counter. Upstairs were “rubber goods, surgical instruments, and miscellaneous stock.” As opening souvenirs, the store gave away “a handsome leather cigar case to male customers and a combination mirror, powder puff, and puff box, containing a high grade of face powder, to customers of the feminine sex”—baubles that would probably sell very well on eBay if they were still around 100 years later.

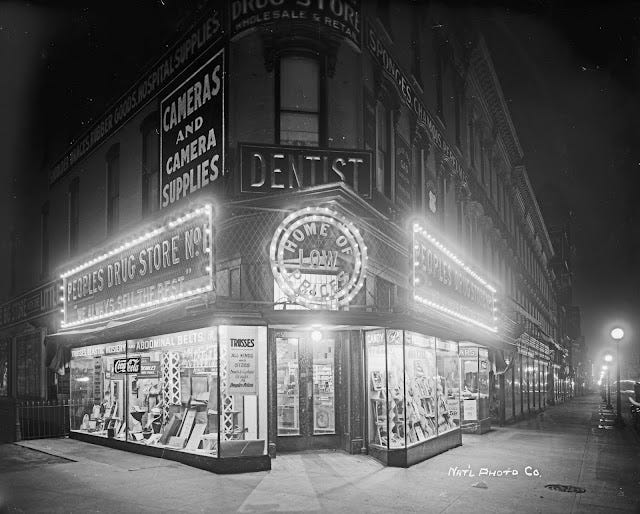

As noted in The Bulletin of Pharmacy in 1922, Gibbs had gone to great pains to design his 7th and K Street store as a giant advertisement for his goods. The plate glass windows at street level extended almost to the ground and were packed with enticing displays. “You can't miss the display from the sidewalk and can even see it from an automobile or passing street-car,” marveled the Bulletin. “It is just like a page in a paper,” Gibbs is quoted as observing.

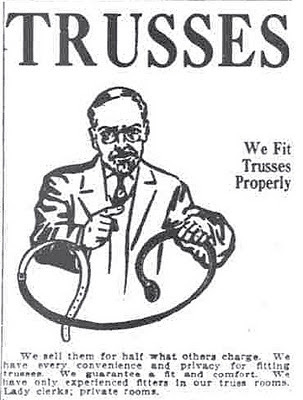

With the enactment of the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906, profound changes had been underway in the drug business. The so-called “patent” medicines (which generally were not patented at all) could no longer contain dangerous ingredients such as alcohol, cocaine, and morphine unless clearly labeled. Sales of items that contained such substances began to decline. However, there was still plenty of room to market all sorts of dubious concoctions, and People's seems to have carried them all. One of my favorites is the perplexingly-titled "Earle's Tasteless Hypo-Cod with Wild Cherry Malt and Iron," billed as a "palatable strength-creating reconstructive tonic" to be taken when recovering from a "long wasting illness," such as the flu. Another item heavily promoted was Buchu Buttons, pills to cure kidney problems. Using a People's coupon, you could get a 50-cent box of Buchu Buttons for just 14 cents in 1911. And while in the store, you could pick up Kornox for your corns, a little Walnutta hair stain, some Graham's blood purifier, and of course Sanitol tooth powder. While these might seem less than appealing to the modern shopper, there were other more toxic choices as well. The May 7, 1911, edition of The Washington Herald advertised “Iron, Quinine, and Strychnine” potion at 47 cents a pint, “Chloroform liniment” at 25 cents for 4 ounces, and “Belladonna plaster” at just 10 cents a packet. Caveat emptor!

In 1912, Peoples opened at its second location, 7th and E Streets NW. Two more stores were added four years later, at 7th and M and at 14th and U. Peoples had gained its reputation as a scrappy discount store on the eastern side of downtown. A turning point came in 1919, when Peoples took over the W. S. Thompson drugstore at 15th and G Streets NW, across the street from the Treasury Department. Thompson’s was a much more sophisticated establishment than Peoples; it advertised itself as the "pharmacy of the Presidents," having served the White House continually since 1857. To some it was almost sacrilegious for an upstart like Peoples to absorb the venerable Thompson's, and in fact it took several years for the marriage of the two institutions to work out. In the process, the Peoples staff learned a lot about the importance of providing scrupulously dependable prescription services.

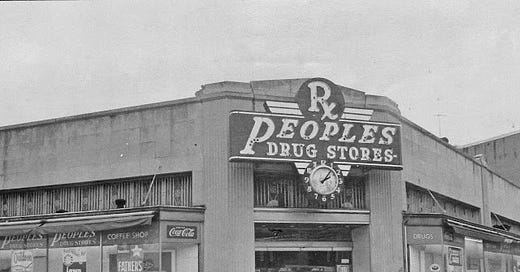

From here Peoples began opening stores in the city's wealthier neighborhoods, such as Mount Pleasant in 1922. More stores would be added at a steady rate for decades to come. Like other retailers, Gibbs kept pushing his stores to be live, hyper-kinetic advertisements for themselves. When the new Peoples store at 13th and F Streets opened in 1927, the Post noted admiringly that it was "fully electrified" with over 2 miles of wiring. The signs outside, with raised opal letters and flashing amber borders composed of 225 individual light bulbs, proved difficult to ignore. By the time of its 50th anniversary in 1955, the chain had 155 stores in 7 states.

Peoples wasn't the first drug store to have a soda fountain, but it was certainly one of its biggest promoters. Across the country, the heyday of the drug store soda fountain was from the 1920s to the 1950s, and it made going to the drug store on the corner as much fun as dropping in to the neighborhood bar. Soda fountains originally dispensed just cool carbonated drinks and ice cream, but beginning in the 1920s, Peoples' soda fountains also offered sandwiches, cakes, and pies, offering stiff competition to lunchroom chains like Childs' and Thompson's. And they continued to grow. In September 1943, amidst wartime staff constraints, People's store #38 on Connecticut Avenue was the first to convert its three soda fountains into the equivalent of a full-blown cafeteria. By 1965, the soda fountain at the 15th and G Street store, the heir to the old Thompson's store, was big enough to accommodate 84 diners.

In 1977, the Washington Star's Pat Lewis chronicled a day in the life of the soda fountain at Peoples store #11 on Capitol Hill, "the last of the old-fashioned Peoples soda fountains," complete with amiable down-and-outers such as the "67-year-old man, unshaven and in tattered clothes" who ordered a coffee and doughnut and then told the waitress to "put it on my bill." "My check comes next week," he explained. Others at the counter were sitting next to each other as they had done every day for years, and Lewis discovered that they didn't even know each other's names. A Catholic University professor came in and sat at the counter, and his breakfast was silently put in front of him, without his having to order anything. The waitress knew what he wanted.

After decades of success, everything was changing at Peoples in the 1970s. Founder Malcolm Gibbs had died back in 1944, and, while continuing to expand, the chain had lost its dynamism. In 1974, an Ohio-based drug store chain, Lane Drug Corporation, gained a controlling share of Peoples' stock, and within a year Ohio-native Sheldon W. (Bud) Fantle (1923-1996) moved to Washington to become chairman and chief executive of Peoples, which the Washington Star-News called a "big but ailing chain."

Fantle set about reinvigorating Peoples with the same kind of zest that Mac Gibbs had embodied in the early days. He overhauled the stock at each store, tailoring it to local area's best-selling items, and began a campaign of aggressively purchasing other drug chains. Old stores were overhauled with the latest 1970s decorations. At a special ceremony in July 1975, Fantle was joined by Mayor Walter Washington at the grand reopening of the flagship store at 15th and G, freshly decked out with bright, headache-inducing wallpaper (see the photo below). It's not known how long that wallpaper lasted.

Soon Peoples was once again an industry leader, and Fantle was seen as masterful turn-around artist. But the changes were not all easy or appreciated. One by one, the beloved soda fountains, for example, were being closed. Fantle said they could no longer compete with the fast-food restaurants that were sprouting up everywhere. In 1988, a Georgetown resident upset about the closing of the local soda fountain, suggested in the Post that the name of the company be changed from "People's" to "Corporate's."

By the 1980s, all three of DC's drug store chains—Peoples (by far the largest), Dart Drug (founded by Herbert Haft in 1954), and Drug Fair (owned at the time by Sherwin-Williams)—were experiencing hard times. The big grocery chains, Giant and Safeway, had discovered that by opening their own pharmacies they could steal much of the drug stores' business, and the competition was withering. The Canadian firm Imasco, Ltd., acquired Peoples in 1984, only to see its profitability plummet over the next three years. In 1987, Fantle left the company and soon took over its ailing competitor, Dart Drug. Dart had developed a bad reputation, and Fantle worked to give it a new image, renaming it Fantle's. It didn't work; the Fantle's chain closed in 1990, after just two years.

That same year, New York-based Melville Corporation acquired Peoples. Melville was a large retail holding company that also owned the 811-store CVS drugstore chain. The new owners kept the Peoples name for several years, but in 1994, after a survey showed that most people wouldn't object to a change, the 89-year-old brand was abandoned, and the former Peoples stores all got CVS signage. Another homegrown retail icon of 20th-century Washington had become extinct.

Special thanks to Faye Haskins and Derek Gray of the Washingtoniana Division of the D.C. Public Library for their invaluable assistance.