A diplomatic retreat on Meridian Hill

Meridian International Center occupies two exquisite mansions designed by John Russell Pope.

Meridian International Center is celebrating its 65th anniversary this year as it continues to restore and enhance its two mansions on Crescent Place NW, just off 16th Street. Built in 1912 and 1922 respectively, the White-Meyer House and Meridian House, both designed by famed architect John Russell Pope, are grand mansions for high-style living and entertainment. They were the homes of two career American diplomats, and today they serve in part as welcome centers for hundreds of foreign diplomats coming to Washington.

Sometimes called “America’s first career diplomat,” Henry White was born in 1850 into a wealthy Maryland family that owned a Southern-style plantation just outside of Baltimore, called Hampton (now a National Park Service site well worth visiting). He was educated in France and as a young man hobnobbed with European aristocrats as a fox hunter in England. After he married New York socialite Margaret “Daisy” Stuyvesant Rutherford, he entered the foreign service, becoming a trusted diplomatic aide to Teddy Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson. He served as ambassador to Italy and to France. Later, he was one of five US peace commissioners who signed the Treaty of Versailles.

No ordinary house was going to do for such a man, so White turned to John Russell Pope, one of the pre-eminent architects of his generation, for his dream house project. Pope designed elegantly restrained, conservatively classical mansions for the rich and famous, especially those with ties to the diplomatic community. Avoiding Gilded Age excess, he set the tone for elite Washington houses in 1909 with his house for Sallie Reynolds Hitt on Dupont Circle. Sadly demolished in 1970 and replaced by a boxy brick-and-glass office building, the Beaux-Arts Hitt House—restrained yet projecting power and status—undoubtedly influenced Henry White’s decision to have Pope design his own house on Meridian Hill.1

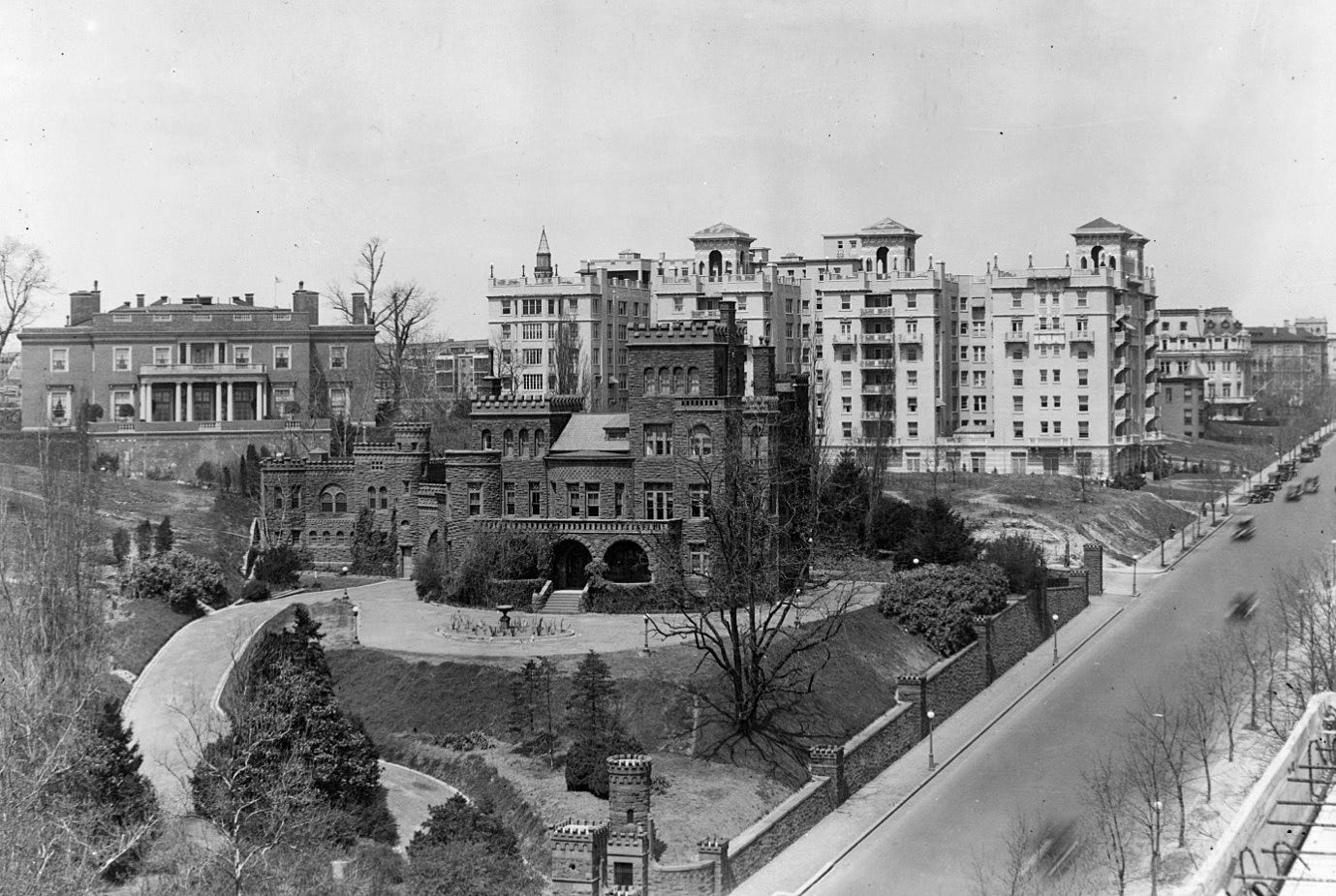

Sixteenth Street on Meridian Hill was increasingly an elite enclave for diplomats and the wealthy, thanks to the strenuous efforts of Mary Foote Henderson. Henderson lived with her husband, former Senator John Brooks Henderson, in a sprawling brownstone “castle” overlooking 16th Street and Florida Avenue that they had built in 1888. Henderson heartily approved of Ambassador White purchasing a lot adjacent to her own in 1910 for his grand retirement mansion.

Almost precariously overlooking Henderson Castle, the White mansion had tremendous views south toward the city. In the distance, the other White House could be seen at the base of 16th Street. Visitors to White’s sprawling, Georgian Revival party house arrived under a columned porte cochère and entered into a grand reception hall lined with more columns. Additional large reception rooms, lounges, and a wood-paneled library wound around to a large formal dining room in the rear. At one end of the dining room hung a stunning full-size portrait of Margaret White, executed in bravura style by John Singer Sargent (and now in the National Gallery of Art). White’s daughter-in-law, Elizabeth Moffat White, later remarked, “Mrs. White used to dominate that dining room—you know the portrait. I would sit right under it and feel (laughing) so inadequate.”2

After Henry White died in 1927, the house was rented to Eugene Meyer, a prominent banker who bought it a few years later, shortly after purchasing the Washington Post. Though decoratively restrained, the White mansion was apparently not restrained enough for Meyer, who stripped away the Ionic columns and presidential busts that originally lined the house’s grand entrance hall. No imperial grandeur for him. Nevertheless, the house remained one of Washington’s social centers, thanks in no small part to Meyer’s wife, Agnes, a passionate art collector and political activist. The Meyers hosted many distinguished guests here, including Eleanor Roosevelt, Thomas Mann, Chief Justice Earl Warren, and John F. Kennedy.3

Lively as its reception rooms were, the Meyers prized the retreat-like quality of their Meridian Hill roost, and by the 1940s, Eugene Meyer was said to have found the old Henderson Castle across the street a nuisance. A Texan named Bert L. Williams had purchased the sprawling brownstone pile in 1937 and converted to the “Castle H Swim and Tennis Club,” with a bar in its ballroom and rooms-to-let upstairs.4 The club attracted a raucous, noisy crowd at night, prompting complaints from neighbors. In 1949, irritated by the late-hour revelry, Meyer bought the dilapidated castle and tore it down. He gained not just peace and quiet but also an enhanced view over the city. Meyer’s daughter, Katherine Graham, would later preside over the Washington Post’s golden years, when the newspaper stood up to a deeply corrupt Nixon administration with reporting that ultimately led to its demise.

Meanwhile, Henry White’s friend and fellow diplomat, Irwin Laughlin, had purchased the adjoining lot in 1912, when the White-Meyer House was under construction. He wasn’t ready to build his own residence until he retired in 1920, when he also turned to John Russell Pope to fulfill his dreams. Unlike White, Laughlin was a Francophile, and he had a vast collection of 18th century French art. He wanted a Louis XVI-style chateau to show off his art, and Pope obliged, despite rarely working in that style for other residential commissions.

The result was another grand entertainment space, completed in 1922. The house features a dramatic double-curved staircase leading up to the main entertainment floor. Here a central, mirrored gallery adjoins large rooms for socializing. One of the most striking spaces is the green, wood-paneled library that originally housed Laughlin’s vast collection of rare books. While the dining room on the opposite side of the house lacks a John Singer Sargent portrait, it more than makes up for it with a huge 17th-century Mortlake tapestry. In fact, the room’s proportions were dictated by this tapestry, one of Laughlin’s prize possessions. Overall, the house is more decoratively embellished than White-Meyer but still elegantly restrained, in John Russell Pope’s signature style. “From the standpoint of both taste and magnificence, the mansion at 1630 Crescent Place is perhaps the finest house ever built in Washington,” wrote commentator Hope Ridings Miller in her Great Houses of Washington, D.C.5

The Laughlin mansion came to be known as Meridian House, and it remained in the Laughlin family until being put up for sale in 1958. Daughter Gertrude Laughlin Chanler was pleased when the non-profit Washington International Center, forerunner of the current Meridian International Center, expressed interest in moving to the house from downtown. With Mrs. Chanler’s help, the center purchased the house in 1960 and has been headquartered there ever since, completing a major renovation in 1994.

After Agnes Meyer’s death in 1970, the White-Meyer House was leased to Antioch College for use as the library of its new law school. Then, after more than a decade, the house came up for sale again in the late 1980s. This time Meridian International Center acquired it, undertaking an extensive renovation in 1987 to return the house to its previous role as host for diplomatic meetings, receptions, and other events.

Tightly enclosed behind tall brick and limestone walls, Meridian House and the White-Meyer House can be difficult to appreciate from the street. They are often bustling with activity, with more than 150 staff working in offices (mostly former bedrooms) on the upper floors, while receptions and meetings take place downstairs. Though not open to the general public on a regular schedule, the houses nevertheless are available for special events, and tours can be arranged.

—Want to take a peek inside? See some of the White-Meyer House’s most interesting features with Joe Himali on Instagram. Or tour the Meridian House library with Joe here.

Special thanks to Danielle Najjar and Riley Nelson of Meridian International Center for their gracious assistance.

Steven McLeod Bedford, John Russell Pope: Architect of Empire (Rizzoli, 1998), 59.

Quoted in Natalie Shanklin, Meridian: Grounds of Diplomacy (Meridian International Center, 2022), 37.

Shanklin, 47-50; Elsie Carper, “Agnes E. Meyer: Writer, Critic, Champion of Reform,” Washington Post, Sep. 2, 1970, A12.

“Henderson Castle Now Is Club, Washington Post; Jun. 4, 1937; 20.

Hope Ridings Miller, Great Houses of Washington, D.C. (Whitehall, Hadlyme, & Smith, 1969), 189.