A final 1912 homecoming for victims of the USS Maine

Most had been brought back in 1899, but some languished on the sea floor for 14 more years.

In January 1898, President William McKinley sent the USS Maine, a four-year-old armored cruiser, to Havana, Cuba, as a show of force to protect American interests as the Cuban War of Independence raged. Less than three weeks later, as the ship docked in Havana harbor, it suffered a massive explosion in its forward powder magazines, ripping away a third of the vessel and rapidly sinking it to the harbor floor. Of the ship’s crew of 355, 261 were killed. The cause of the explosion was likely accidental, but the tragedy was said at the time to have been caused by Spain. “Remember the Maine! To hell with Spain!” was the rallying cry as the Spanish-American War began.

The war was over within months, and in 1899 the remains of most of the victims, which the Spanish had buried in Havana, were exhumed and brought back to the United States. A solemn reburial ceremony was held at Arlington National Cemetery on December 28, 1899 for 150 sailors.

But the ship still lay at the bottom of Havana Harbor, its main mast jutting out of the water. Veterans commemorating the sinking of the Maine in 1910 clamored for the ship to be raised and the bones of the remaining dead returned to the US for proper burial at Arlington. Congress approved a measure to do just that, and in 1911, the Army Corps of Engineers built a cofferdam around the sunken hulk, drained it of water, and then carefully sifted through the wreckage, both for human remains and for clues about the explosion that killed them. The investigation confirmed that the explosion occurred in powder magazines in the forward section of the ship, but it drew no conclusion as to what caused the magazines to ignite. Most people were convinced that a Spanish torpedo was responsible.1

By the time work concluded in January 1912, the remains of 64 unidentified individuals had been retrieved from the wreckage. The engineers were able to seal and re-float the rear third of the ship (the rest was in pieces), and they took it out to international waters and re-sank it. Meanwhile, the remains of the 64 victims were placed in 34 coffins and brought back by ship to the Washington Navy Yard.2

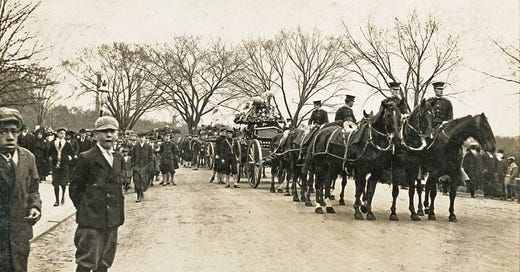

The solemn funeral for the last Maine victims was held March 23, 1912, with all major government officials in attendance, including President Taft, cabinet members, Supreme Court justices, senators, and members of Congress. Several squadrons of sailors and marines accompanied the 34 caissons, each drawn by six horses, as they marched up Pennsylvania Avenue from the Navy Yard. Crowds of silent onlookers lined the route. However, the solemn procession wasn’t without incident. As the horse-drawn caissons approached 14th Street, an out-of-control automobile careened up the street and crashed into a streetcar on Pennsylvania Avenue that had stopped directly in front of the procession. The driver, a real estate agent named Robert Stevens, was arrested for failure to maintain control of his vehicle. No one was hurt, but the horses were rattled, and it took some doing to calm them down before the procession could continue on its way.3

The procession finally arrived at the south terrace of the State, War, and Navy Building (now the Eisenhower Executive Office Building), where a ceremony was planned before proceeding on to burial at Arlington National Cemetery. But just as President Taft stood to speak, a passing storm swept through, unleashing a barrage of hail that pelted all the bare heads (the men had doffed their hats in respect for the dead). Someone offered the president an umbrella, but he brushed it away and proceeded unfazed with his solemn eulogy.

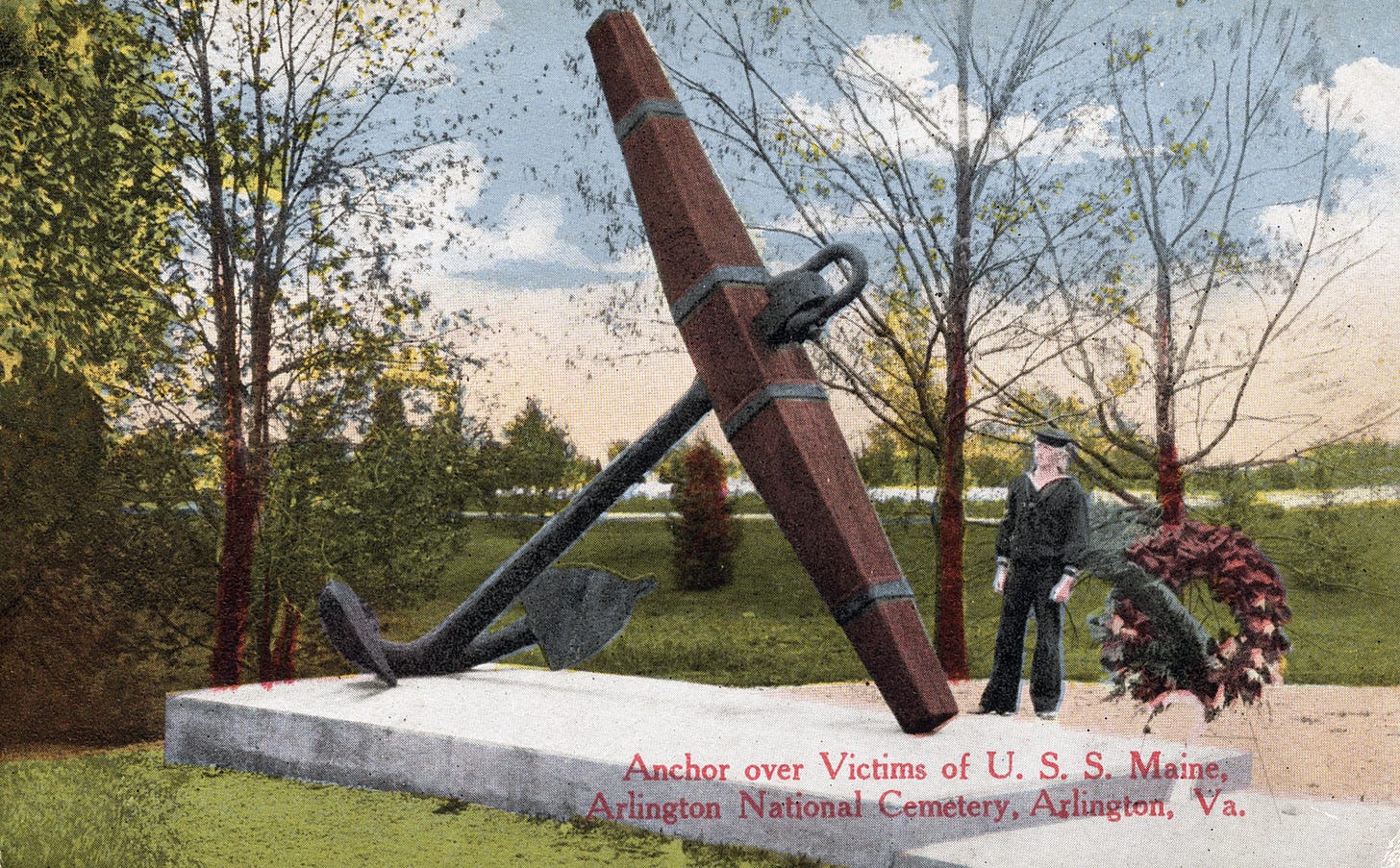

The hail gave way to a steady rain as the elaborate cortege marched “through a sea of mud” six miles to Arlington Cemetery. According to the Washington Post, “the rain increased in intensity, and when the President stepped under the flimsy canvas that had been erected as a shelter for him, he stood bare-headed beneath a tent that leaked from every seam.” No one but the reporter appeared to take note of the weather. The coffins were laid in open graves, alongside those of their comrades who had been buried in 1899, on a hillside where one of the ship’s anchors stood (and still stands) as a memorial. One sailor stood at attention at each grave as it was filled. “Eventually the entire plot was studded with sailors standing bare-headed in the rain.” The event concluded with a booming 21-gun salute from Fort Myer’s cannons.4

As part of the effort to raise the wreckage of the Maine and collect its human remains, Congress authorized retrieving the ship’s main mast and bringing it home to erect as a permanent memorial at Arlington. In 1915, the new memorial was completed, with the restored mast proudly installed on a stone base structure designed by architect Nathan Wyeth.

“To Solve Fate of Maine,” Baltimore Sun, Aug. 30, 1910, 5; “Wresting the Tragic Secrets of the Maine from the Sea",” Washington Post, Sep. 3, 1911, 11.

“Maine’s Dead Here,” Washington Post, Mar. 21, 1912, 1.

“Auto Nearly Hits Caskets,” Washington Post, Mar. 24, 1912, 2.

“Nation Honors Dead of Maine,” Washington Post, Mar. 24, 1912, 1.

Yes, as always, John, you share such interesting and often moving moments of history related to our hometown. Your effort is so appreciated.

Excellent piece. Thanks.