Appreciating the HUD (Robert C. Weaver) Building and its Modernist legacy

A few Brutalist buildings, notably this one, are iconic

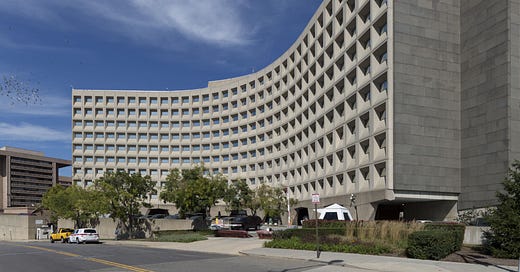

The Trump administration has expressed a desire to relocate the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) from its historic Robert C. Weaver headquarters building, at 7th and D Streets SW, which it plans to sell. The landmarked building, designed by celebrated Modernist architect Marcel Breuer, is one of the city’s best Brutalist structures and an icon of its era—when the federal government’s intended role as a force for social good was expressed in powerful and innovative architecture.

President John F. Kennedy famously was troubled by the dilapidated condition of the north side of Pennsylvania Avenue that he observed during his inauguration parade in 1961. He formed an ad hoc advisory committee to come up with recommendations on how to improve federal architecture. As part of the committee’s work, then Assistant Secretary of Labor Daniel Patrick Moynihan developed a set of Guiding Principles for Federal Architecture. The Principles stated that federal buildings, in part, should “provide visual testimony to the dignity, enterprise, vigor, and stability of the American Government,” using “designs that embody the finest contemporary American architectural thought.” The guidelines pointedly declared, “the development of an official style must be avoided.” The HUD building was the first major federal office building in DC designed and constructed in conformity with these principles.1

Born in Hungary, architect Marcel Breuer was a student of Walter Gropius at the pathbreaking Bauhaus in Weimar, Germany in the 1920s. After working in London, he moved to the US in 1937, where he reunited with Gropius at Harvard University. Breuer influenced a generation of American architects with his Modernist ideas and was highly respected with the US government chose him to design the new building for the federal housing agency, which would soon be elevated to cabinet level. For the HUD building, Breuer partnered with his associate, Herbert Beckhard, a Princeton-trained architect who worked with Breuer on many projects in the 1960s.

Construction began in 1965. The site, in the Southwest Urban Renewal Area, was chosen as a sign of the federal government’s commitment to urban renewal. The sprawling, dog-bone shaped building is full of Expressionist verve. In their highly regarded survey of the buildings of Washington, DC, architectural historians Pamela Scott and Antionette J. Lee wrote that walking around the building “provides an experience in architectural movement and drama that lifts [the building] dynamically above its surroundings.”2

Indeed. The structure is perched on 44 massive W-shaped concrete piers (or pilotis) that raise the mass of the building off the ground—a frequent Modernist motif. The giant piers create tension and evoke the strength and resolution needed to permanently suspend the building’s mass in the air. The main load-bearing walls consist of arrays of precast-concrete, modular window units. (This was the first Federal building in the United States to use precast concrete as the primary structural and exterior finish material.) The units feature deeply recessed windows with angled concrete frames. It is as if a vast array of giant eyes is looking out at the world, imagining how to build it up for the future.

President Lyndon B. Johnson spoke at the building’s dedication in September 1968, emphasizing how it represented a sea change in government architecture. “The drab, gray Government building, I hope, has finally had its day,” he said, calling on Americans to create a nation that “will always be like this building—bold and beautiful.”3

The New York Times’ architecture critic, Ada Louise Huxtable, was happy the building was not “some half-baked adaptation of the grandeur of the past,” as had happened so often when architects relied on tired, neoclassical motifs. “The house that HUD built is a handsome, functional structure that adds quality design and genuine 20th-century style to a city badly in need of both,” she wrote, adding, “We have spent too many decades mistaking the superficial forms for the essential spirit and forfeiting the Capital’s greatness.”4

Of course it’s not perfect. Like all buildings, it has needed adaptations as circumstances have changed. When it opened, the General Services Administration—the federal government’s real estate manager—saved money by bringing in secondhand furniture from other buildings and by taking over the design of most of the interior spaces, cutting them up into drab and uninspired office warrens.5 But problems like that could be corrected (and still can) without sacrificing the building’s exterior grandeur.

Contemporary aesthetics are obsessed with glass and metal. New architecture is relentlessly light and insubstantial, frequently with blindingly white interior spaces. Accustomed to these trends, some viewers can be intimidated by the Herculean mass of a Brutalist masterpiece like the Weaver building. (It was renamed in 1999 for Robert C. Weaver, the first Secretary of HUD and the first African American cabinet member.) There are certainly plenty of other Brutalist buildings that did not achieve the same expressive power and are little more than concrete bunkers. Many have already been reskinned or demolished, and more will surely follow. But the Weaver building is iconic, a fierce statement of the values and aesthetics of a bygone era. We should appreciate and preserve it as we move into an uncertain future.

Special thanks to Carol Highsmith for taking such beautiful photographs of the Weaver Building and so many other DC buildings and donating them to the Library of Congress for all of us to use and appreciate.

Robinson & Associates, Inc., Growth, Efficiency and Modernism: GSA Buildings of the 1950s, 60, and 70s (General Services Administration, 2003), 42-5.

Pamela Scott and Antionette J. Lee, Buildings of the District of Columbia (Oxford Univ. Press, 1993), 239.

“Johnson Dedicates HUD Offices,” Washington Post, Sep. 10, 1968, C1.

Ada Louise Huxtable, “Architecture: The House That HUD Built,” New York Times, Sep. 22, 1968, 129.

Wolf Von Eckhardt, “4300 Under One HUD Roof,” Washington Post, Sep. 7, 1968, B2.

This is a wonderful essay, John. It almost (but not quite) makes me appreciate Brutalist architecture! The HUD Building is indeed iconic and Highsmith's photos are fabulous, but I generally find Brutalist architecture to be cold and off-putting. I used to teach at UDC, and that campus always felt barren and lifeless, one concrete bunker after another.

There is an exhibit on Brutalism around the DC area, called Capital Brutalism, that is well worthwhile. At the National Building Museum through June 30th.

https://nbm.org/exhibitions/capital-brutalism/