Bread For The City: Shaw's Historic Bakeries

The renaissance of the greater Shaw neighborhood in recent years has drawn attention to the rich cultural history of places like the U Street entertainment strip and the elegant residences of LeDroit Park. However, the area also had its thriving industrial side, once hosting factories that produced much of the bread, cakes, and other baked goods bought by Washingtonians in the early decades of the 20th century. Brand names based in Shaw, such as Dorsch's, Corby's, and Holzbeierlein's, all now forgotten, were once staples of Washington households. Even after national corporations—the Continental Baking Company and the General Baking Company—took over much of the D.C. market, their baking operations remained anchored in Shaw.

Dorsch's White Cross Bakery (photo by the author).

One of the most visible reminders of the neighborhood's bakery heritage is the former Dorsch's White Cross Bakery at 641 S Street, NW, now standing vacant and forlorn as it waits for redevelopment. This property is just a half block east of 7th Street NW, Washington's commercial artery a hundred years ago. The oldest section of the building was built in 1913 as an expansion to an existing bakery run by Peter M. Dorsch (1878-1959) at 1811 7th Street NW. Dorsch had previously worked at bakeries with his younger brothers at various locations in D.C., including K Street in Southwest, Virginia Avenue, and Georgetown, before settling on the upper 7th Street site for his own business. Born in D.C., he was the son of a Bavarian immigrant, Michael Dorsch, who had come to Washington in the 1870s and sold imported German foods before opening a restaurant on 7th Street (perhaps where his son later had his bakery). Peter clearly inherited his father's business acumen, and as his White Cross Bakery prospered, he gradually acquired adjacent real estate at the S Street location until his factory became a sprawling complex of retail space, a baking plant, and various stables and garages for delivery wagons.

Prominent today on S Street are the façades of the buildings Dorsch put up in 1915 and 1922. The shorter of the two is from 1915, designed by the firm of Simmons & Cooper, with space for a store in front and baking operations to the rear. The taller 1922 building, of similarly utilitarian form, was designed by A.B. Mullett & Co., specifically Frederick W. Mullett (1869-1924), the son of famous architect Alfred B. Mullett, who committed suicide in 1890.

Photo by the author.

Both buildings have emblematic white crosses prominently displayed on their pediments. It's surely no accident that the crosses have the same proportions as the American Red Cross's famous logo. At the beginning of the twentieth century, food sanitation had become a nationwide obsession, culminating in Upton Sinclair's famous The Jungle, about the horrors of the meatpacking industry. Bread-making was also a topic of concern. An article in the New York Times in 1896 excoriated small traditional bakeries in that city ("The walls and floors are covered with vermin, spiders hang from the rafters, and cats, dogs, and chickens are running around in the refuse...") and asserted that "the cause of this trouble is that small bakeries are owned by ignorant persons. The large bakeries are conducted in an exemplary manner."

A delivery truck in front of the factory in 1923. Source: Library of Congress.

It seems to have been part of a campaign to get people to buy all their bread from large factories. An 1893 article in the Evening Star observed that "Home-made bread is a back number. Machine-made bread takes the cake. The twentieth century bakery is a thing of beauty and the up-to-date baker is a joy forever." At the popular Pure Food Show at the Washington Convention Hall in 1909, D.C. bakeries put on a massive exhibit that filled the K Street end of the hall. Visitors could observe machines doing the work in a modern factory setting; dirty human hands never touched the bread. In that same vein, a 1919 advertisement for Dorsch's in The Washington Times urged consumers to give up their old-fashioned reliance on the corner store: "Why buy bread at the grocer's, fresh for each meal, when it is possible to get good, wholesome, and fresh bread that tastes as good at the last bite as it did when you first cut into the warm loaf?"

Ad from the June 11, 1919 edition of The Washington Times.

Dorsch's advertised "Old Mammy's Rice Bread" and "Old Mammy's Real Raisin Bread" to a customer base that presumably wasn't troubled by the racist overtones. Their biggest competitor was the Corby Baking Company, makers of "Mother's Bread," which had its factory just up the street at 2301 Georgia Avenue NW. Corby's had been founded by Charles I. Corby (1871-1926) and his brother William (1867-1935), who were born in New York and moved to Washington around 1890. Charles started the first small bakeshop on 12th Street NW and was soon joined by his brother. In 1894 they borrowed $500 for a down payment to buy a bakery on Georgia Avenue. After construction of a new building in 1902 and additions in 1912, the complex filled much of the block and soon ranked as Washington's largest bakery.

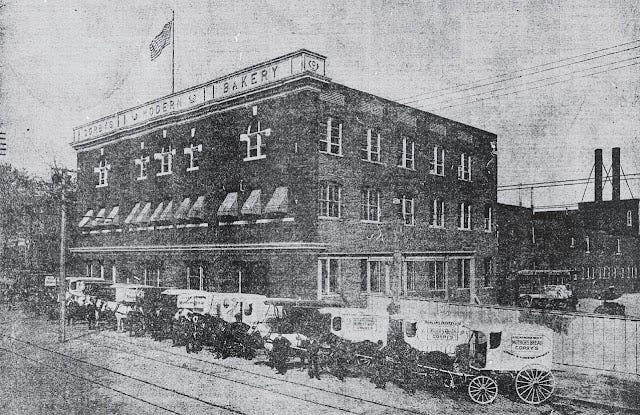

Photo of Corby's Bakery from the January 28, 1906 edition of The Washington Times

The Corby's building today. Photo by the author.

The Corby brothers focused from the start on automation, patenting a number of processes and machines for producing bread of a uniform quality previously unknown. An article in the October 1915 edition of Baker's Review marveled at the Corby bakery's high-speed mixers with their automatic counters, the dough slides and six-pocket Duchess dough dividers, the Thomson moulders, the Werner & Ffleiderer rounders. At that time, 165 people were on the payroll at Corby's, including 60 bakers. Up to 90,000 loaves of bread and 2 1/2 tons of cakes were produced each day, and these were sent to the far corners of the District via 52 wagon and 8 automobile routes, the on-site stables housing 96 horses. The self-contained factory had its own power plant, well, and refrigerating plant. It even built, painted, and maintained its own wagons.

Laboratory at the Corby Baking Company, circa 1922. Source: Library of Congress.

Charles and William Corby both became fabulously wealthy and acquired lavish mansions in Montgomery County. William's sprawling Tudor-style estate at 9 Chevy Chase Circle was called Ishpiming; Charles purchased the Strathmore Hall estate at Rockville Pike and Tuckerman Lane. Charles, who had a heart ailment, fell dead in the grandstands of the Nautilus polo field in Miami Beach, Florida, in February 1926, only a year after retiring from the baking business. His son, Karl W. Corby (1893-1937), who took over after his father's retirement, likewise had heart trouble and likewise died suddenly in February while in Florida.

Not nearly as big as Corby's, Holzbeierlein was located in the same block as Dorsch's, at 1849 7th Street, NW. It was founded by Michael Holzbeierlein, a German immigrant, in 1893. It sold bread and cakes under the "Famous" label and later featured "Bamby" bread. Like Dorsch, Holzbeierlein had his retail bakery on 7th Street and larger baking and distribution facilities nearby, on Wiltberger Street. A newspaper advertisement from 1908 included this charmingly vapid jingle:

Famous Bread and famous Cake,

Famous everything they make;

That's the motto and the sign

Of the famous HOLZBEIERLEIN.

The Holzbeierlein business remained family-owned throughout its history. It declared bankruptcy in 1953, unable to compete with low-cost national brands. It had 70 employees and 30 delivery trucks at the time it folded.

Ad from the July 26, 1908 edition of The Washington Times.

National brands began taking over the Washington market as early as 1911, when the General Baking Company was formed in New York City by merging prominent bakeries from all over the east coast and the Midwest. In Washington, the Boston Baking Company joined the new conglomerate and began producing Bond Bread in its bakery at the foot of Capitol Hill. The new product was called Bond Bread because each loaf had General Baking Company’s guarantee printed on its wrapper, warranting that “the loaf of bread contained within this germ and dust proof wrapper is made from the following pure food materials, and no other ingredients of any kind: best spring wheat flour, compressed yeast, pure filtered water, best fine salt, pure lard, cane sugar, and condensed milk.” However, by 1928, the government was planning to take over the bakery's site to relocate the U.S. Botanical Garden there from the center of the Mall, so General Baking was forced to search for a new location.

Company officials chose a site on Georgia Avenue in Shaw about a block and a half south of the Corby bakery complex and on the west side of the street. This location offered excellent transportation connections for employees to get to work as well as for the delivery of the bakery's finished product. Opposite, on the east side of Georgia Avenue, stood Griffith Stadium. For years to come, attendees at ball games would be treated to the sweet smells of the Bond Bread factory wafting over them as they sat in the stadium's bleachers. Excavation work at the bakery site began in 1929 for the $650,000 state-of-the-art building, designed by Corry B. Comstock (1874-1932) of New York, an experienced bakery architect. An article in the Evening Star noted that the building would be one of the largest and most modernly equipped in Washington. “Particular attention will be paid to sanitary measures, the bread being touched by human hands only twice in the baking and once in the wrapping.” It was completed in 1930.

The Bond Bread factory. Photo by the author.

Of all the historic Shaw bakery buildings that remain standing, the Bond Bread Building is the most distinctive. At a time when many new factory buildings were nondescript, the General Baking Company clearly sought a distinguished look for its Georgia Avenue plant. The brick-and-concrete building's stepped, three-level façade is in keeping with art deco design practices, which favored ziggurat-like shapes. Its sleek vertical piers with their pointed stone caps at the roof-line signal a touch of the soaring optimism of the art deco age, though the building is not actually very tall. The clean, white-glazed finish accentuates the message that Bond Bread is pure and healthful. The structure's design evokes the "stripped classical" or "traditionalized Moderne" style typical of later federal Washington buildings—the verve of art deco checked by the constraints of neoclassicism. The main entrance, for example, is purely neoclassical and could work as well on a bank as a bread factory. The overall message, though restrained, is of pride and permanence.

By moving to this location, General Baking was squaring off directly with its biggest rival, the Continental Baking Company, which had taken over the Corby bakery in 1925. Continental replaced Corby's Mother's Bread with its new Wonder Bread product, which was rapidly gaining in popularity. In October 1925, the company, still using the Corby's name, advertised "a delicious new Cake Dedicated to the women of the nation's Capital! In homage to them named Hostess Cake!" It's not clear where the Hostess name actually originated, but it soon became the brand for all of Continental Baking's cake products. The company further expanded by buying Dorsch's White Cross Bakery in 1936, giving it a combined capacity at its two locations of 200,000 loaves of bread each day. It seems likely that by the 1940s, the company made Wonder Bread primarily at the former Corby's bakery and Hostess Cake products at the White Cross site.

The 1930s saw bread marketing begin to shift away from the sensationalism about sanitation fears to focus more on nutritional benefits. General Baking upped the ante in 1931 when it licensed patents for fortifying its Bond Bread with vitamin D, the sunshine vitamin. Continental responded by adding even more nutrients to Wonder Bread, eventually culminating in the famous "Builds Strong Bodies 12 Ways" slogan. In 1973 the Federal Trade Commission barred ITT Continental Baking from running ads that implied that Wonder Bread was more nutritious than other bread or could spur growth in children.

Wonder Bread continues to be produced, of course, now by Hostess Brands, Inc., which bought Continental Baking in the mid 1990s. The former Corby complex was shut down in 1988 when Continental Baking decided to consolidate regional operations in a larger, newer facility in Philadelphia. The company used the Corby complex for a couple more years as a distribution facility, then sold it to developer Douglas Jemal, who converted the old bakery buildings for retail and office use. Howard University then purchased the Wonder Plaza complex in 1993 for $18.3 million.

Jemal also purchased the former Dorsch's White Cross Bakery, complete with bright "Wonder Bread" and "Hostess Cake" lettering on its historic façade. The property has come to be known as the Wonder Bread Factory, and Douglas Development Corporation is currently developing it into an apartment building with about 80 small units. The building hosted the D.C. Preservation League's 40th anniversary celebration in 2011.

Bond Bread factory entrance. Photo by the author.

Meanwhile, the Bond Bread Building will likely be altered in the near future. In the 1960s, General Baking Company's profit margins slimmed to the point where bread-making was no longer profitable. The company renamed itself General Host in 1967 and gradually shuttered its bakeries to concentrate on other forms of retail. By 1971, the Georgia Avenue plant had shut down and was purchased by the D.C. government for use as a community services center.

The 1971 arrangement provided the District with federal funds to renovate the old bakery and run the community services center in it jointly with the People's Involvement Corporation, a federally-financed anti-poverty group that was given a 30-year tenancy. Mayor Walter Washington verbally promised PIC that it could take ownership of the building at the end of that period, but by 2001 the District had other plans. Specifically, the D.C. government proposed giving the property to Howard University, which planned a development there called Howard Town Center, a mix of housing and retail. In exchange, the university would give the District a parcel at Florida and Sherman Avenues, where a separate project of offices, retail and housing would be developed. PIC sued to gain ownership of the building based on the Mayor's original promise, but it lost in court. Meanwhile the deal with Howard was ratified by the city council in 2006 and completed in 2008. In December 2012, applications were filed with the D.C. government to demolish both the Bond Bread Factory as well as the historic bus garage next door, an elegant brick building designed by Arthur B. Heaton (1875-1951) and completed shortly after the bakery. However, the D.C. Preservation League filed nominations to protect both sites, and on May 23, 2013, the Historic Preservation Review Board designated both as historic landmarks, requiring the developer to obtain Board approval for any changes to their exteriors.

Kim Williams of the D.C. Historic Preservation Office provided valuable assistance for this article.