Chinatown's Friendship Archway, landmark from an earlier era

A cultural statement celebrating local and international heritage

Much of DC’s Chinatown is about symbols. The neighborhood is small and fragile, seemingly forever on the brink of extinction. Its identity as a destination hinges on a smattering of things Chinese: the restaurants, the red and green lampposts, the Chinese characters on street signs. Without a doubt the most striking and enduring symbol is the Friendship Archway, constructed in 1986 just east of 7th and H Streets NW, and said to be the largest in the world when it was constructed. Boldly symbolic of Chinese identity, this project was plagued by controversy when it was built over what sort of China it symbolized.

Chinatown originally developed in the late 19th century around Pennsylvania Avenue NW at 4 1/2 Street (now John Marshall Place). Chinese immigrants to the U.S. in those days faced discrimination and hostility; the creation of Chinatowns in Washington and elsewhere in the country was as much a defense mechanism as anything else—a way to create safe havens where new immigrants could find shelter, sustenance, and employment. Washington’s original Chinatown was forcibly displaced in 1931 when the land was taken over by the government for the Federal Triangle and other municipal projects. A new replacement Chinatown was established (against the wishes of local businesses and landowners) along H Street NW between 5th and 7th.

By 1981, however, Chinatown seemed on the verge of extinction. Successful Chinese Americans, like many others, had dispersed to more prosperous parts of the city and the suburbs. Chinatown still had a cluster of restaurants and grocery stores, but the decline of the old downtown area made many wonder whether such commercial establishments would remain viable in the future. Two Chinatown leaders, Dr. Dwan L. Tai and Alfred H. Liu, wrote a paper entitled “The Future of Washington's Chinatown: Extinction or Distinction,” in which they argued in favor of creating a visible attraction, such as an archway, to serve as a magnet for visitors. The idea began to gain traction.

In May 1984, Mayor Marion Barry and other top city officials took a trip to Beijing, and the dreamed-of archway project finally got its start. Beijing Mayor Chen Xitong had visited Washington the previous fall, and Barry was returning the favor to promote Washington as an international business and finance center. After surviving a welcoming banquet that included fish stomach and beef tendon soup, Barry went on to participate in a ceremony establishing Washington and Beijing as sister cities. As part of the agreement, the two cities would work together on a project to build a traditional archway in Washington’s Chinatown. The principal designer would be Alfred Liu, one of the authors of the white paper and a well-established architect and chairman of the Chinatown Development Corporation. Liu had emigrated from Taiwan as a teenager and had designed Chinatown’s Wah Luck House, an apartment building for low-income and elderly residents on 6th Street.

The archway plan immediately stirred controversy. A contingent of prominent Chinatown businessmen objected to the participation of the communist People’s Republic of China in the project, many of them having strong ties with mainland China’s rival, Taiwan. The Washington Post quoted Lawrence Locke, chairman of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association of D.C., as saying that the archway “might misidentify the local Chinese community with the Chinese communists.” Locke reportedly collected more than 50 signatures from Chinatown residents and businessmen on a petition opposing the project. Locke also reportedly claimed to have assembled $250,000 in pledges for a separate project to construct an arch without any involvement of the mainland Chinese government. The arch’s opponents had enough clout to get their city council representative, John Wilson, to introduce a resolution opposing the arch’s construction.1

In July 1985, a resolution of sorts was reached: there would be two arches in Chinatown, both on H Street, two blocks apart. The Friendship Arch to be built in cooperation with the People’s Republic of China would be located, as originally planned, just east of 7th Street. A rival Chinatown Community Arch would be constructed two blocks away, just west of 5th Street. The Chinatown group promoting the second arch wanted to put it at the other end of Chinatown—9th and H Streets, near the old convention center. In fact, they might even build two arches to serve as gateways at either end of Chinatown. In the end, however, the plans never came to fruition; doubts were raised about the wisdom of investing scarce funds in “rival” arches, and neither of the competing arches were built.2

The finished archway, or paifang in Chinese, is an impressive engineering achievement, standing 47 feet tall at the top of its highest roof, spanning 75 feet of roadway, and weighing over 128 tons. The roofing alone weighs 63 tons, supported by 27 tons of steel and 38 tons of concrete. Over 7,000 glazed tiles cover its five roofs, and 35,000 separate wooden pieces are decorated with 23-karat gold. A riot of dragons, 12 carved and 272 painted, glare and grin from every angle. The style is evocative of the classic Qing dynasty (1649-1911), a period when China showcased its imperial splendor. Indeed, paifangs were traditionally erected across alleys and roads throughout China, with the more elaborate ones, like Washington’s, often to celebrate the emperor on the occasion of one of his military victories. The golden color of the tile roofs on the Washington archway is symbolic of wealth and honor, as were the yellow mandarin jackets bestowed as a supreme honor on Qing officials.

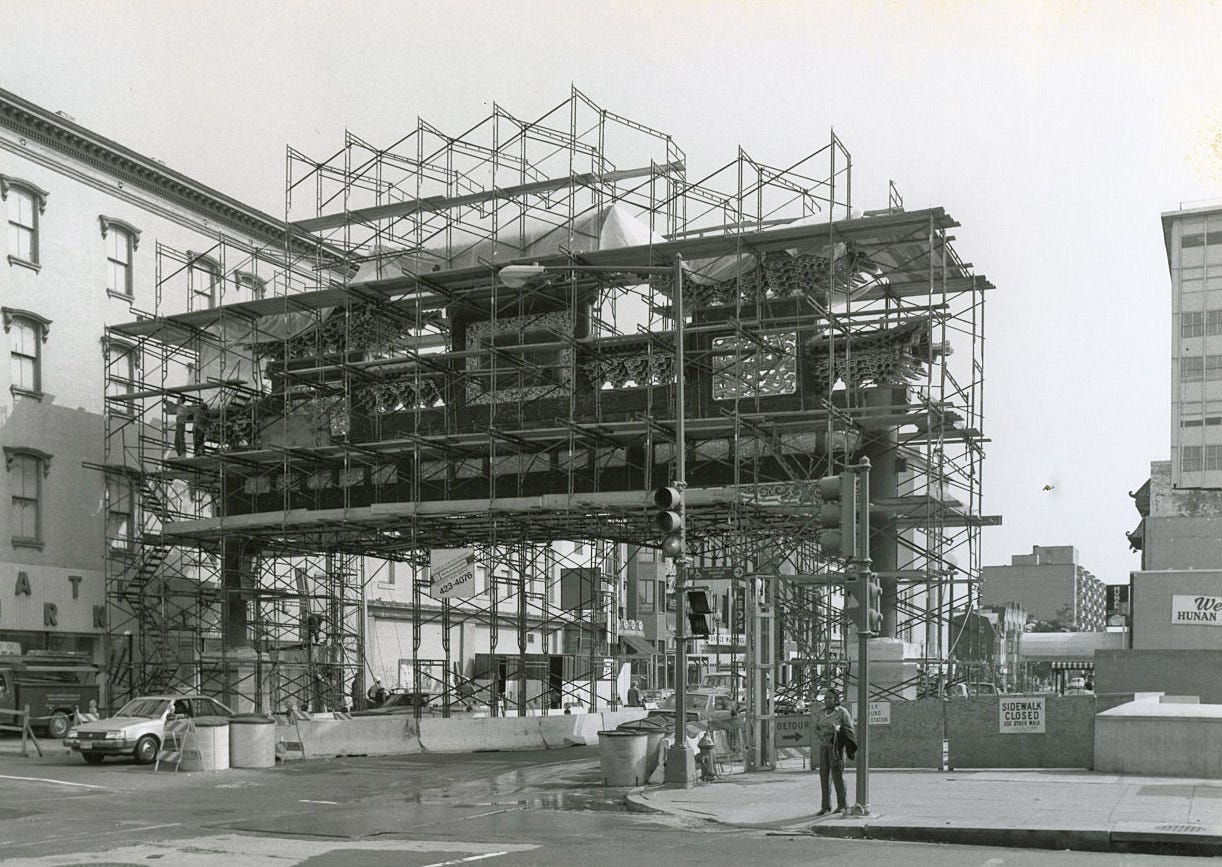

Construction began in June 1986. The District first built the reinforced concrete frame and supporting pillars based on Liu’s design. Major decorative elements, including the 7 pagoda-like roofs, were fabricated in China and installed on the arch by 16 skilled Chinese craftsmen brought to Washington by the D.C. government under the supervision of Liu. The Beijing Ancient Architectural Construction Corporation was in charge of work in China, including fabrication of the 59 intricate dou gong supports—complex, cantilevered contraptions of carved wooden brackets, balanced and interlocked with tenons and mortises rather than nails or screws and providing a sturdy and resilient support for the gracefully curved roofs. The dou gongs have a very festive appearance, almost like frilly Victorian bloomers peeking out from beneath the golden skirts of the roofs.

In ancient China, these elaborate structures were painted to protect the wood from the elements. By the time of the Ming and Qing dynasties, the painting had become an opportunity for magnificent polychrome displays. One of the chief tasks of the 16 artisans brought to Washington was to apply red, blue, and green paint; gold leaf; and other finishing touches by hand. The arch was constructed over a 7-month period, much of the work needing to be done at night so as not to block traffic on busy H Street. The finished monument was officially dedicated in November 1986.

Once completed, the archway was widely celebrated, and the political squabbles about how it should be built soon died down. The giant monument seemed almost shockingly bright and festive. Linda Wheeler, writing in The Washington Post, called it “a brilliant multicolored flower transported into a drab landscape.” Benjamin Forgey, the Post’s architecture critic, observed that “Simply put, before the gateway there was not much to remember Washington’s dwindling Chinatown by, and now there is.... It is a fitting, striking, and quite beautiful object.” Forgey saw the archway as a signpost for the major tourist attraction that Chinatown could become. But that was still an unrealized dream in 1986. The arch’s magnificence contrasted starkly with the drab landscape then surrounding it.3

Both the archway and its neighborhood have had ups and downs in the years since its construction. In 1989, after the crackdown by Chinese authorities in Tiananmen Square, the city council enacted a resolution suspending relationships with sister-city Beijing. Council chairman David A. Clarke personally climbed a ladder to drape black mourning cloth on the Friendship Archway to commemorate the students killed in China.

Soon, the archway unexpectedly began to deteriorate. It turns out much of the mortar used to set the tiles in the roofs did not bond correctly. According to Liu, this was due to the fact that the Chinese artisans’ visas were delayed, forcing construction to continue into October, when cold weather compromised the mortar. In any event, tiles began to fall off within several years of the archway’s completion. In June 1990, a 100-pound ornamental dragon fell from the arch, landing on the roof of a soda truck.

DC workers secured the archway, removing the remaining tiles as a safety measure until permanent repairs could be made. In 1993 a major renovation project was undertaken, funded by both the DC and Chinese governments. Artisans from the same Chinese company that had worked on building the arch again traveled to Washington to perform extensive repairs, including re-laying tiles with improved mortar, repainting decorations, and reapplying gold leaf. Since that time, there have been no more problems with falling tiles.

After many years, the paint applied in 1993 became quite faded. In 2009, a second repainting and modernization project was undertaken with funding from the D.C. Commission on the Arts and Humanities. The entire archway was sanded and repainted, and several pieces of tile and wood were replaced. In addition, a new lighting system was installed, using energy-efficient LED lights. In 2020, additional conservation work was performed to clean and repaint the arch, restore cracking and loose tiles, and replace non-functioning lights.

The brilliant, vivid archway stands at the crossroads of a vibrant downtown community. The adjacent Gallery Place Metro station connects several major subway lines with crosstown buses that ply H Street underneath the arch. Sports fans and other event goers have flocked to the nearby Capital One Arena since it opened in 1997, bringing business to restaurants and shops. Before the pandemic struck in 2020, the neighborhood was constantly bustling, but by 2022, the chilling effect of the pandemic and a spike in crime led many to question the neighborhood’s safety. Thankfully, crime has since been reduced, and plans are afoot to revive the area, the centerpiece being an $880 million redesign of the Capital One arena.

The Friendship Archway remains a lasting symbol of the neighborhood’s shared heritage and a celebration of the city’s rich multicultural fabric—the very thing that makes our city, and the nation, enduringly great.

A version of this article first appeared on Streets of Washington in 2011.

Invaluable assistance for this article was provided by Alfred H. Liu, A.I.A., President of AEPA Architects Engineers, P.C. Other sources included Asian Voice, Friendship Archway Inauguration Edition (Nov. 1986); Francine Curro Cary, ed., Urban Odyssey: A Multicultural History of Washington, D.C. (1996); James M. Goode, Washington Sculpture (2008); and numerous newspaper articles.

Carlyle Murphy, “Arch Plan Widens D.C.-Chinatown Rift,” Washington Post, Jul. 31, 1984, B7.

Kenneth Bredemeier, “2 Chinas Will Span H Street,” Washington Post, Jul. 16, 1985, A1.

Linda Wheeler, “Gilding Chinatown’s Arch,” Washington Post, Oct. 23, 1986, DC1; Benjamin Forgey, “Archway of Triumph,” Washington Post, Jan. 31, 1987, G1.

I continue to enjoy every post. Excellent scholarship.