Garfinckel's, Washington's Best Dressed Department Store

If you were White, Garfinckel's was the place to go for the latest fashions.

The retail enterprise founded by Julius Garfinckle in 1905 was a relative latecomer to the city's department store field. Woodies, Lansburgh’s, the Palais Royal, Kann’s, Goldenberg’s, and Hecht’s all were established by the 1890s, making for a saturated and highly competitive market by the turn of the new century. But Garfinckle's store (he later changed his and the store's name to Garfinckel) carved out a unique, high-end niche and held on to it for 85 years, cultivating generations of dedicated shoppers who depended on the store for the trendiest and classiest apparel. When Garfinckel's finally declared bankruptcy and closed in 1990, it was a heart-wrenching experience for employees and customers alike.

Born in Syracuse, New York, Garfinckle went to Colorado as a young man, hoping to strike a fortune in silver mining. Instead he became a clerk in a dry goods store. He moved to Washington in 1899, where he found employment with Parker, Bridget & Company, a prominent fashion-oriented dry goods store at 9th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue NW. As a buyer for that store's women's clothing department, Garfinckle traveled frequently to New York and learned all the ins and outs of the retail fashion industry.

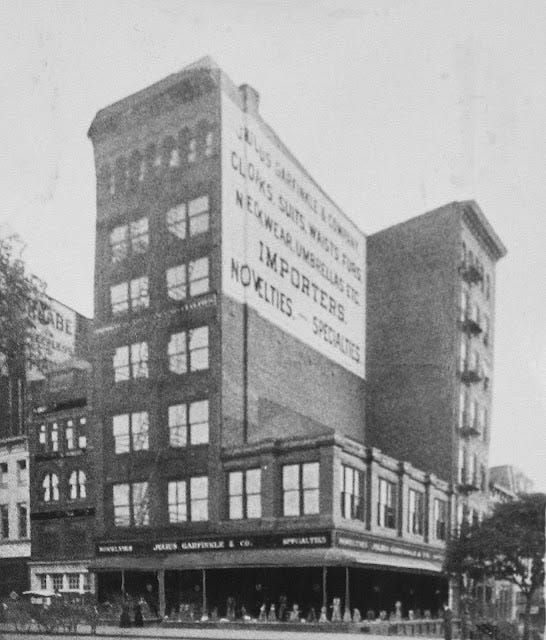

In 1905, Garfinckle set out on his own with the founding of his namesake store, which occupied the bottom floor of a seven-floor building at 1226 F Street NW. With his Parker Bridget experience and contacts, Garfinckle filled his new store with “a carefully selected stock of women’s suits, cloaks, furs, &c, together with imported novelties and specialties,” according to the Washington Post, which observed that the new store’s “popularity is already assured.” In keeping with the expectations of his high-end customers, Garfinckle made sure that each received personal attention.1

The Post's early prediction of success soon came true. Garfinckle’s gradually filled all seven floors of its host building, an odd-looking structure that was originally half-built to allow for future expansion. Within a few years Garfinckle’s booming business led him to take over the two-story space on the corner previously occupied by Brentano’s bookstore and then to build out the missing floors above it.

But even that complete building wasn’t big enough, and by the 1920s, after Garfinckel changed the spelling of his name, he had his sights set on constructing a grand new building better fitting his prestigious business. He began assembling as much property as he could at the northwest corner of 14th and F Streets NW, and in 1928 announced plans for an imposing new 8-story building.

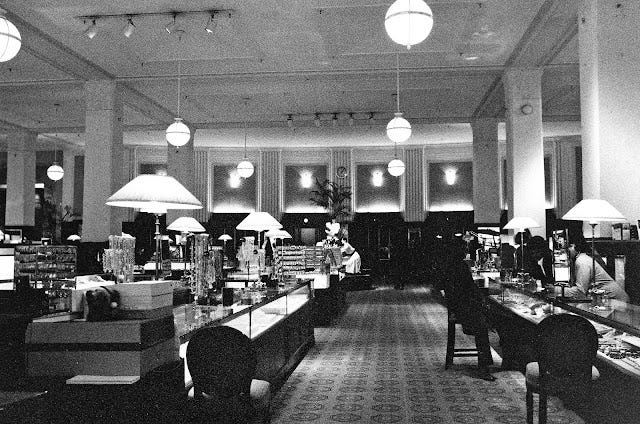

The beautiful Garfinckel’s building, which Mrs. Herbert Hoover officially opened in October 1930, reflected the store’s carefully cultivated air of sophistication. Designed by the New York firm of Starrett and Van Vleck (no lowly Washington architect would do for this building), its stately limestone façade was in a restrained classical style, embracing the clean lines of art deco but avoiding unseemly exuberance. Inside it sported the latest amenities, including a “scientifically” controlled system of cleverly hidden ducts and vents that would provide both warm air in the winter and cool air in the summer as well as cold storage for the furs of Washington’s most fashionable women and a system of conveyor belts for sending parcels down to delivery vans.

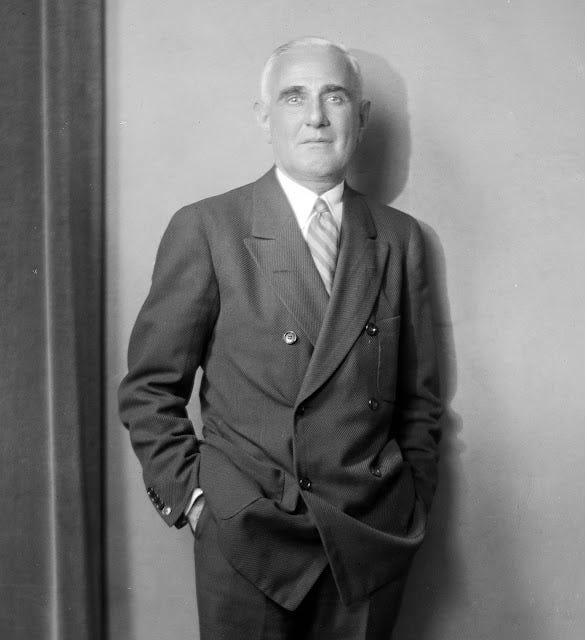

Julius Garfinckel, the lord of this fiefdom, was by all accounts a very likable individual. Everyone said he had a great sense of humor, and he made a point of walking the entire store and visiting with each employee every day. He knew and asked about everybody’s family members. He was similarly charming and attentive with all his customers, even going out of his way at times to see to their individual needs. If he were in Paris on a buying trip, for example, he might select a special dress for the planned wedding of a customer’s daughter. Loyal customers came to revere Garfinckel and defer to him without question in matters of fashion and taste, making him a rock star in DC’s small world of haute couture.

Garfinckel was distinctly eccentric as well, but that only added to his mystique as a fashion arbiter. He never attended dinner parties or other social events. As the National Register nomination for the Garfinckel’s building explains, “He was reportedly a teetotaler and a vegetarian, who stood on tiptoes when talking to customers to compensate for his small stature, and rushed to wash his hands after shaking hands with visitors.” Never married, he lived first in an apartment at the Burlington Hotel at 1120 Vermont Avenue NW and later in a suite at the exclusive Hay-Adams Hotel on Lafayette Square. His sole known diversion was horseback riding, and he could be seen at times on the trails of Rock Creek Park. President Calvin Coolidge, another famously reserved individual, sometimes accompanied him.

Single-mindedly dedicated to his store, Garfinckel worked long hours and often on weekends and holidays. He took advantage of the eighth-floor setback on his new building and had his desk placed outdoors under an awning on the balcony from early spring to late fall. Distracted reporters in the National Press Building opposite could watch in fascination as an endless parade of pretty women would come out on the balcony to model new clothes for Garfinckel’s personal approval. He was as uncompromising as he was eccentric, insisting that Garfinckel’s be the exclusive outlet for any and all of its merchandise. He instructed his managers to immediately discontinue any item found to be on sale at another DC store.

When Garfinckel died in 1936 after a bout with pneumonia, the loss was widely lamented. While noting that he was “of a retiring disposition” and “not particularly socially inclined,” The Post noted that his obvious business accomplishments “did not overshadow his outstanding work in many civic and charitable organizations and movements in Washington.”2 His philanthropic streak was borne out in his will, which left the bulk of his $6 million fortune to charity, including the YWCA, which was to establish a home and school, named after his mother, to support “worthy women under the necessity of earning their own livelihood.” The Harrison Center for Career Education continues to this day as a component of the local YWCA.

Garfinckel had been the sole owner of his store, and after his death changes inevitably occurred, included an eagerly anticipated public stock offering in 1939 that was to pay very well for its savvy investors. The store changed in subtler ways as well. Garfinckel had insisted that the mannequins in the display windows be headless and armless because he thought full human figures distracted from looking at the clothes; this policy was soon dropped after his death.

Ultimately, the only way to be truly exclusive is to exclude people, and Garfinkel’s, like many other Washington institutions of its day, did just that. It was a whites-only enterprise until forced to give up the policy by the success of the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 60s. Speaking to the New York Times in 1988, Elsie M. Monroe, who came to Washington in 1951, remembered the store bitterly: “I am from Richmond, the Gateway to the South, and I never remember being turned away from a store there. But Blacks could not shop at Garfinckel’s... You had the money; the money was the color green, but your money would not spend in that store.”3 Boycotted along with other downtown department stores in the late 1950s, Garfinckel’s didn’t hire its first African-American clerks until the early 1960s. Many Blacks refused to shop at Garfinckel’s even after it dropped its discriminatory practices.

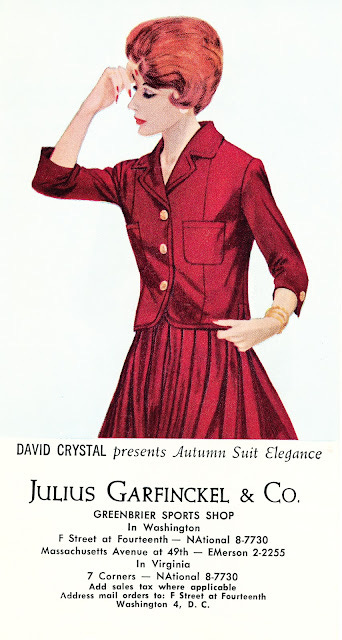

Garfinckel’s had its best days in the 1940s and 1950s. An article in the New York Times in 1961 called it the arbiter of tastes in the capital and rattled off all the famous people that had been outfitted there, beginning with Mrs. Theodore Roosevelt and including all the first ladies through the elegant Jackie Kennedy.4 Visiting queens and other dignitaries shopped there as well. A bevy of models was once sent to Blair House so that King Saud of Saud Arabia could see a special collection of fur coats on live models. Mrs. Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Mollie Parnis dress came from Garfinckel’s, as did Mrs. Robert Kennedy’s Christian Dior and Norman Norell dresses. Even Mme. Hervé Alphand, wife of the French Ambassador, had her hair done at the Garfinckel salon.

Garfinckel’s opened its first branch store in Spring Valley in 1942 and steadily expanded into the suburbs beginning with a store at the Sevens Corner Shopping Center in Virginia—the first suburban shopping mall in the DC area—in 1956. Garfinckel’s would eventually have eight locations throughout the region. The company also started acquiring other businesses beginning in 1946 when it bought Brooks Brothers, the prestigious New York clothier, from the great great grandson of Henry Sands Brooks, who had opened his first store in 1818. The company later bought the DePinna fashion stores, also in New York City, and a Richmond, Virginia, department store chain, Miller & Rhoads, in 1967, which made the company as a whole larger even than Woodies in sales volume. Then in 1977 it acquired the Ann Taylor chain, a trendy fashion retailer that had been founded in 1954.

But things began to change in the 1970s as Garfinckel’s executives attempted to “modernize” the venerable store that had lived for so long off of its distinguished heritage and impeccable credentials. Fellow downtown department stores were suffering, and some, including Lansburgh’s and Kann’s, had gone out of business, prompting nervousness about the need to appeal to a broader clientele. Indicative of change were the new “verité” display windows adopted in 1976. Post reporter Nina Hyde observed a Garfinckel’s window laid out with female mannequins dressed in work clothes, a cigarette dangling from the lips of one, a ladder and tools scattered about, and paint splashed on the window. A Garfinckel’s patron in a navy linen suit and pumps passed by. “They've lost their minds,” she remarked.5

And so it seemed they had. The company spiraled into financial peril as management changes put it in serious jeopardy. Even as it made money and talked of further expansion and acquisitions in the late 1970s, it began to “attract the sharks,” as Post columnist Rudolph Pyatt later explained. In 1981, New York-based Allied Stores, Inc., acquired Garfinckel’s in a hostile takeover. Allied, in turn, was acquired by a Canadian firm in 1986, which promptly spun off Garfinckel’s to help pay for the acquisition. Garfinckel’s by this point was languishing, an old-fashioned store with no one to breathe new life into it. As bidders circled, there was talk of selling the majestic building at 14th and F Streets NW, and preservationists grew concerned. Late in 1987 Raleigh’s Stores, Inc., bought Garfinckel’s and promptly fired six of its top executives. Preservationists, including the D.C. Preservation League, ensured that the flagship main building was designated an historic landmark in 1988, but that didn’t stop Raleigh’s from selling the building and leasing back space to keep the store running. Garfinckel’s was fatally unprofitable by then, its assets plundered to finance the wheeling and dealing of corporate raiders. It finally filed for bankruptcy and closed in 1990.

Having embraced the pinnacle of Washington social life for so long, Garfinckel’s loss seemed to mark the passing of an old order. Everyone remembered above all the high level of service, the quality goods. My father used to rave about how expertly the Garfinckel’s staff would fit shoes or suits. Women remembered buying wedding dresses there, being seated and waited upon with elegant fashions brought to them to inspect. All gone. As the Post’s Kara Fisher wrote in June 1990, the store’s going-out-of-business sale was the ultimate insult, a chaotic madhouse of angry customers, blaring orange discount signs, frazzled clerks—everything that Garfinckel’s had scrupulously avoided over its long and distinguished career.6

There followed several years of wrangling over the fate of the store’s landmark downtown building, which was zoned exclusively for use as a department store. Many wanted another department store there, and for a time it looked like Lord & Taylor might move in, but it never came to pass. In 1993, the DC government abandoned efforts to try to get another department store in the space, and recommended that a mixed office/retail use be allowed. Downtown congregations fought the decision in court, arguing that a department store would create more jobs, but lost the case. Redevelopment of the building finally began in 1997, and it reopened as Hamilton Square in 1999. Borders Books moved into the ground and basement retail floors in 2000 and was subsequently replaced by a massive restaurant called The Hamilton in December 2011.

A version of this article first appeared on Streets of Washington in November 2012.

Special thanks to Faye Haskins and Mark Greek of the Washingtoniana Division of the D.C. Public Library and to Bruce Yarnall of the D.C. Historic Preservation Office for their valuable assistance. Other sources included the National Register of Historic Places nomination form for the Garfinckel’s building (1995), William Hogan, “Washington's Merchant Prince” in Regardies (Sep-Oct 1981), and numerous newspaper articles.

“New Store on F Street,” Washington Post, Sep. 3, 1905, 12.

“Funeral Rites For Garfinckel Set for Today,” Washington Post, Nov. 7, 1936, X1.

Marianne Szegedy-Maszak, “D.C.: The Other Washington,” New York Times, Nov. 20, 1988, SM44.

Charlotte Curtis, “Store Is Arbiter of Tastes in Capital,” New York Times, Sep. 15, 1961.

Nina S. Hyde, “Windows Verite: Buying Time With A Slice of Life,” Washington Post, Jun. 7, 1976, C1.

Kara Swisher, “Tempers Rise as Prices Fall at Garfinckel’s,” Jun. 28, 1990, C1.

I worked at the Garfinckel's at Montgomery Mall in about 1971. Having a Washingtonian family used to shopping at the original stores, it was always a little sad when the dept. stores (and people!) abandoned downtown for the suburbs. It makes me sad now to see, when I visit home, how Friendship Heights has changed. Thanks for this article.

I worked at the Seven Corners Garfinkel’s in Greenbrier Sports part time while in high school. After that I was promoted to a buyers clerical and transferred to 14th and F St. I was 18 yrs old. What a wonderful place it was in 1968!