In 1871, Washington celebrated a newly wood-paved Pennsylvania Avenue

"Hoop-de-Dooden-do!" a newspaper headline exclaimed

The muddy, unpaved streets of Washington were once infamous. In Civil War days, everyone complained about the thick muck in wet weather or the choking dust when it was dry. The ruts and potholes made getting across vast Pennsylvania Avenue especially treacherous. But in 1871 that all changed. Pennsylvania Avenue was paved with a fine new surface of smooth wooden blocks, replacing the old dirt and cobblestones. Work had begun in late 1870, and by February it was complete. It was time to party.1

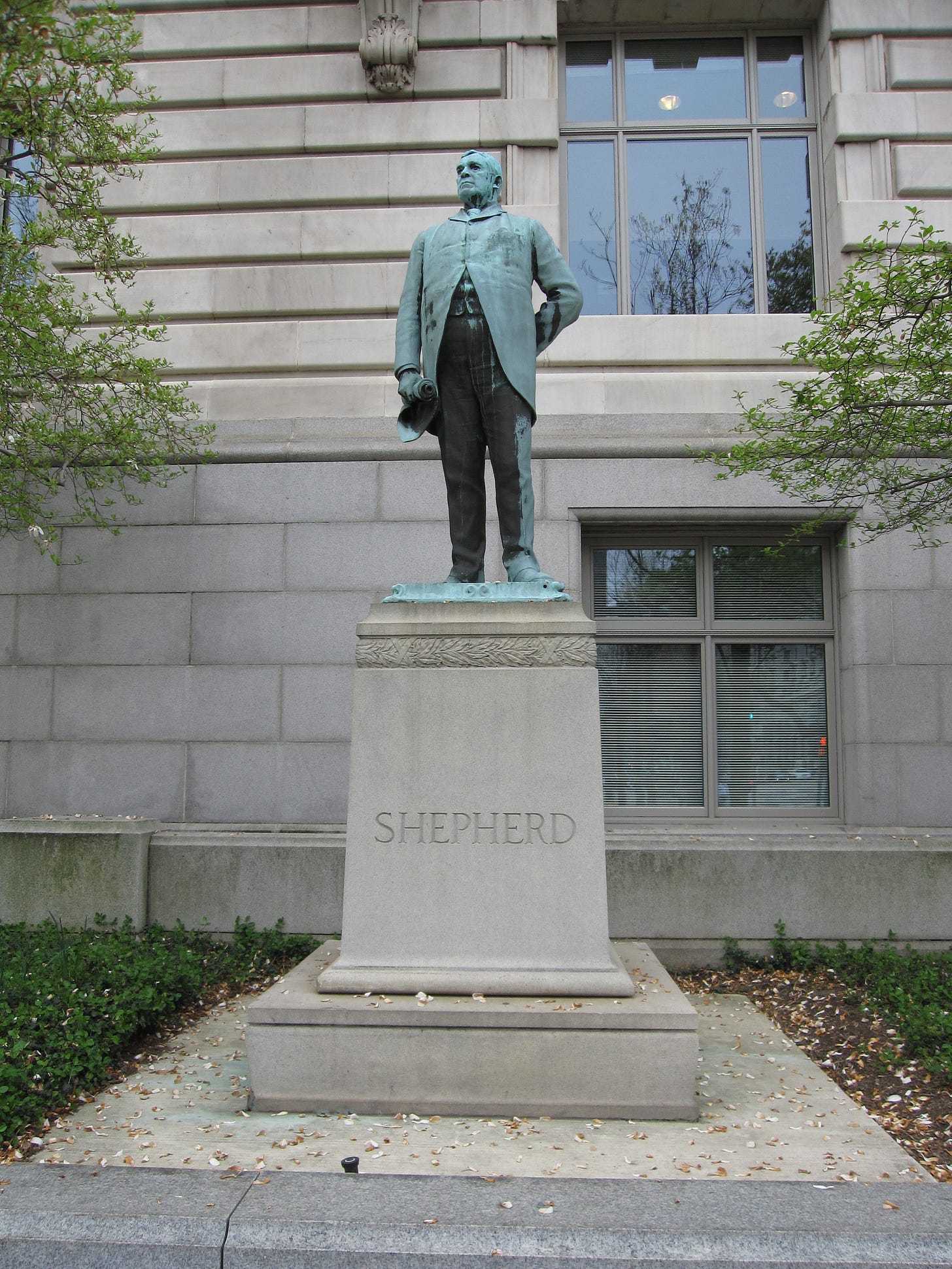

In November 1870, after Congress had just approved the paving project, editors at the local National Republican newspaper proposed a carnival to celebrate the new pavement once it was finished. It would be perfect for street races. A festival in late February, just before Ash Wednesday, would align with George Washington’s Birthday as well as carnival celebrations in other cities. Perfect. An organizing committee was established, and Alexander B. Shepherd, future governor of the Territory of the District of Columbia, took its helm.2

Shepherd, whom detractors would later deride as “Boss Shepherd,” had much to gain from the big event. A gregarious extrovert, the real estate developer and former plumber believed that sweeping citywide infrastructure improvements were necessary to make Washington into a modern city. The paving of Pennsylvania Avenue was just the first step. As de facto head of the soon-to-be-created Board of Public Works, Shepherd would oversee a massive program of grading and paving streets, installing sewers and street lighting, and planting thousands of trees throughout the District. A bill working its way through Congress to reorganize the DC government and establish the Board of Public Works was about to become law. The successful carnival would be a great advertisement for “the new spirit of enterprise which seems to animate our citizens and prompt them to improve and beautify the city, and make it the great social center of the country,” as an Evening Star article explained.3

Shepherd’s committee did everything it could to promote the carnival far beyond the District’s borders. The New York Times reported, “The activity and energy with which the [carnival] scheme has been pushed may be inferred from the fact that a line of railroads as far West as St. Louis has been secured, over which visitors may come and return for fare one way, and the same reduction has been or promised to be made for the South and East.” The carnival committee set up a special welcome center in a building on the Avenue (owned by Shepherd, natch), where visitors would be assisted to find accommodations without being gouged. Among other incentives, a $1,000 prize was promised for the best-drilled military regiment. Horse race winners could look forward to a “fine road wagon” (first place) and gold-mounted harness (second place). “Visitors to the number of many thousands are confidently expected,” the Times concluded, and the prediction would prove accurate.4

Visitors streamed into the city, most coming by train or by steamboat to the Southwest waterfront. Hotels and boardinghouses were filled to overflowing. On the unseasonably warm morning of February 20th, the first day of the event, the Avenue was packed with spectators. The Evening Star reported that the pavement was “as clean as a parlor floor” (a team of 200 laborers had swept it the previous night). Buildings lining the route were festooned with flags, pennants, evergreens, and flowers. Those who could afford it rented seats at windows—one party reportedly paying $75 for two windows between 9th and 10th Streets. A small attic window might go for $5. President Grant was given a suite with a balcony at the St. James Hotel, turning down competing offers from several rivals. He, several cabinet officers, and other dignitaries, including Alexander Shepherd and architect Adolf Cluss, watched from this balcony.

Beginning at 9 o’clock, horse races were run from 2nd to 14th Street, five each day on the 20th and 21st. Prominent business leaders, military officers, and congressmen showed off their steeds. Later in the day, the same mile-long track hosted foot races, bicycle races, mule races, goat races, blindfolded wheelbarrow races, and many other diversions. After the races, the street was opened to pleasure riders, including “sulkies, open buggies, top buggies, phaetons of all kinds, close carriages, open carriages, and almost every sort of vehicle ever seen in this neighborhood.” In a separate later event, knights in medieval costume performed ring jousting atop their colorfully garbed horses.

The police were ordered to keep the Avenue clear of dogs, but they had a hard time of it. Every now and then a few would dart out of the crowd into the street, and the police would give chase. Invariably the crowd cheered the dogs on, enjoying the unscripted show. On the Treasury grounds (pictured above), pickpockets were out in force. One incident: “During the evening a lady felt a strange hand near her pocket and raised an alarm, when the man made off. A young man collared him until the lady came up when she grabbed him by the hair with one hand and with the other made his face smart, he, in the meantime, crying, ‘I haven’t got your pocketbook!’ to which she replied, ‘You would have had it if I hadn’t left it at home.’”5

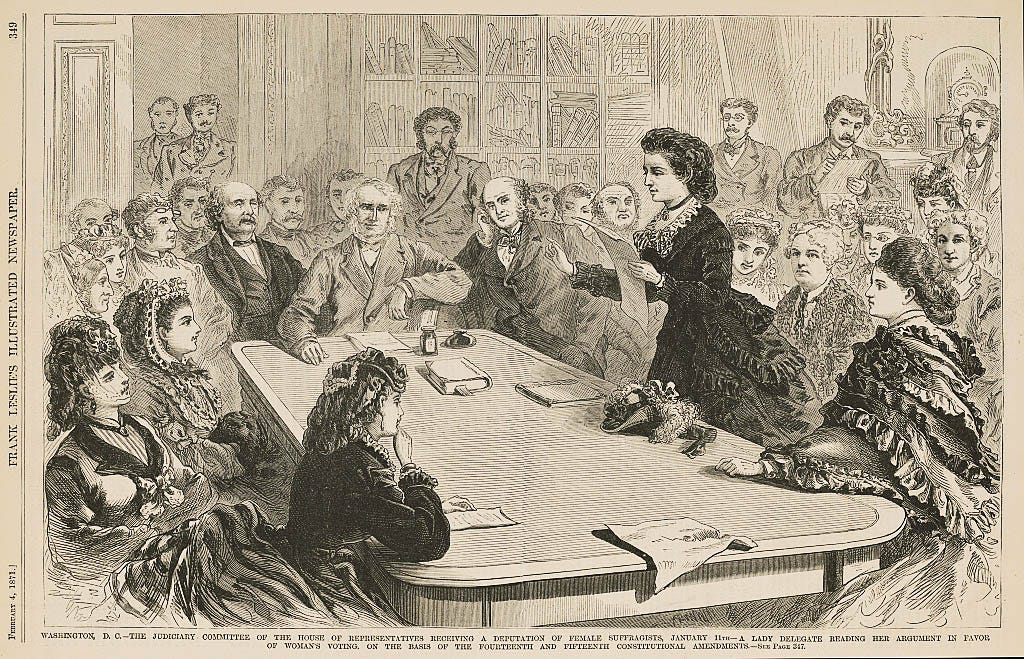

An extravagant “masquerade procession” on the 21st was another part of the festivities—a prelude to the grand masquerade ball held later that evening at the National Theatre. Over 3,000 participants, representing all sorts of storybook characters from Mother Goose to Old King Cole paraded down the Avenue. After them came processions of firemen and other civic organizations, including one sure to stir political passions. The New York Herald had advised readers that “A main feature of the procession is to be a prophetic representation of the inauguration of the female President in 1873.” Indeed, the controversial Victoria Woodhull, an advocate of free love and women’s suffrage, appeared “mounted in a triumphal car” and surrounded by a “guard of honor, consisting of infantry, cavalry and artillery, all [men] attired in female costume.”6 Woodhull was the declared candidate of the newly-formed Equal Rights Party. It’s unknown whether she swayed any onlookers with her provocative display, but she received very few votes in the 1872 election. She would have been too young to serve even if she had won.

After sundown, ten thousand linen Chinese lanterns strung along the Avenue illuminated the crowded sidewalks, supplemented by calcium lights mounted on lampposts. A large fireworks display was set off on the grounds south of the Treasury. The climax of the festivities were the several grand balls held on the evening of the 21st, including the elaborate masquerade ball at the National Theatre and a “civic” ball at the Masonic Hall at 9th and F Streets. Another formal ball at the new Corcoran Gallery of Art (now the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum)—served as a charity event to raise money for the unfinished Washington Monument.7

A good time certainly was had by all. An editorial in the National Republican, after gloating about coming up with the carnival idea, gushed about its success: “It is a complete transformation of the city into a thing of happy life, a gigantic embodiment of merriment, breathing, shrieking and dancing in an ecstasy that is too overpowering for utterance!”8

Overpoweringly ecstatic or not, the carnival was indeed a success. Washingtonians would reminisce about it for years to come, even organizing a permanent carnival association to put on similar, less extravagant events in ensuing years. Shepherd, sometimes called the father of modern Washington, also personally had much to celebrate. On the second day of the carnival, February 21st, Congress passed and Grant signed the District of Columbia Organic Act, which created the city’s new territorial government and established the Board of Public Works that Shepherd would oversee. It was the start of his grand campaign of public improvements.

Under the Board’s supervision, additional streets across the city were paved with wooden blocks, but by the late 1870s it was clear that wood was a poor choice—it rotted too quickly. The streets were repaved, mostly in asphalt. Shepherd’s program of infrastructure improvements also would not last long. By 1874, it had bankrupted the city, and Shepherd himself declared bankruptcy two years later and moved to Mexico. Nevertheless, his achievement was lasting; the nation’s capital would never again be the muddy little town it once was.

Special thanks to Pete Penczer for giving me the idea for this article.

James H. Whyte, The Uncivil War: Washington During the Reconstruction 1865-1878 (Twayne Publishers, 1958), 102-6; John P. Richardson, Alexander Robey Shepherd: The Man Who Built the Nation’s Capital (Ohio University Press, 2016), 89-90.

“Letter from Washington: Proposed Carnival,” Baltimore Sun, Nov. 21, 1870, 4.

“Carnival,” Evening Star, Feb. 20, 1871, 1.

“Washington,” New York Times, Feb. 6, 1871, 1.

“Carnival,” Evening Star, Feb. 21, 1871, 1.

“The Coming Carnival at Washington, New York Herald, Feb. 15, 1871.

“The Rambler Writes of the Avenue Carnival,” Sunday Star, Dec. 23, 1917, 4-3.

“Carnival Sheet,” Daily National Republican, Feb. 21, 1871, 3.

Thanks for digging up some good old news for us in a rather gloomy Washington DC of 2025. Very interesting each part of this article.

Wow, they surely knew how to throw a party in those days. Thanks for the post. Very interesting.