Kate Chase and the lost Salmon P. Chase House

The Hecht Company tore it down in 1936 to build a parking garage.

Once upon a time, on the northwest corner of Sixth and E Streets NW stood a stately Greek Revival mansion, constructed in 1851. During the Civil War, it was the home of Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase (1808-1873), whose image would later grace the $10,000 bill. Chase lived here with his beautiful daughter, Kate (1840-1899), whose marriage to Sen. William Sprague of Rhode Island in 1863 was a highlight for Washington society. Sadly, the house was demolished in 1936, long before historic preservation laws could protect it. Kate’s marriage to William Sprague disintegrated—very publicly—much earlier.

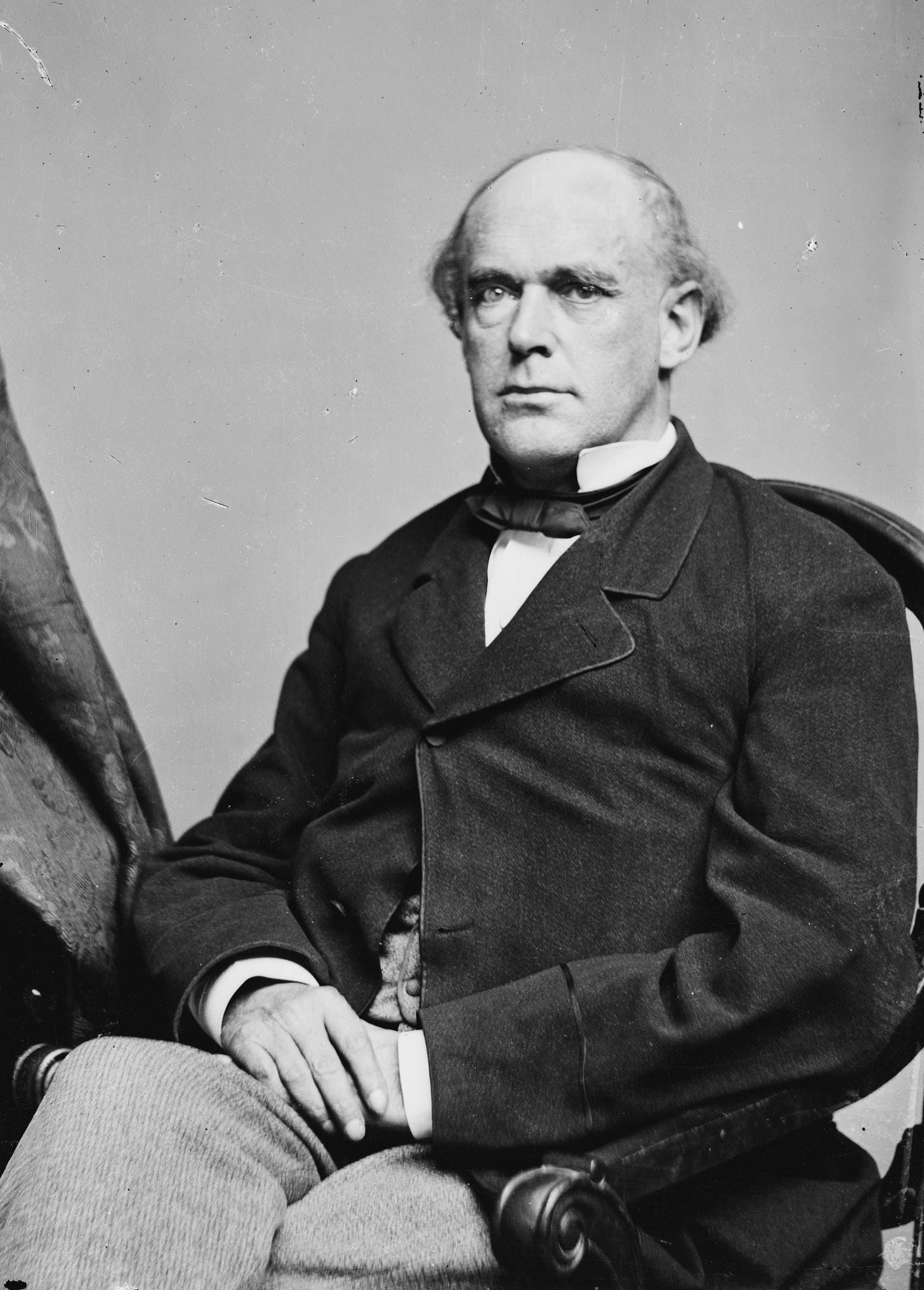

Salmon P. Chase was one of Abraham Lincoln’s “team of rivals,” a cerebral, humorless man who lacked Lincoln’s capacity for empathy and had a “sanctimonious streak that even admirers found off-putting.”1 He did an extraordinary job of managing the nation’s precarious finances during the war. So much so that admirers in New York City named a major bank in his honor in 1877. But Chase, a Radical Republican from Ohio, was also consumed with ambition; he desperately wanted to be president and was chagrined when the Republican Party in 1860 nominated the folksy Abraham Lincoln instead of him.

Chase had suffered enormous personal tragedy. He was married three times, losing all three wives to disease within a few years of marrying them. He likewise lost four young children to disease, but still had two daughters, Kate and Nettie, when he came to Washington as Secretary of the Treasury. While the younger Nettie was away at boarding school, Kate and her father moved in to the elegant house they rented at 6th and E—then a very fashionable residential neighborhood of large houses, many of which were inhabited by lawyers and judges practicing at the nearby D.C. Courthouse.

Living alone with her widowed father, the irrepressible Kate Chase was 21 years old. She quickly established herself as the undisputed queen of Washington society—the “Belle of the North,” as she was called. Strikingly intelligent, poised, and charming, Kate was also scornful of other women and conquered men’s hearts easily. She was captivated by high society, which she navigated with exceptional dexterity, and was particularly drawn to military men. The onset of the Civil War brought legions of interesting Army officers virtually to her doorstep. The Chases even allowed their home to be used for recovering wounded soldiers at one point early in the war.

When the war broke out, regiments of Union volunteers began streaming into Washington. In March 1861, the spacious top-floor galleries of the nearby Patent Office were hastily adapted as a temporary barracks for one such group, the First Rhode Island Regiment. The Rhode Islanders slept in crudely assembled three-tier bunk beds ranged alongside delicate glass display cases filled with patent models.

Accompanying the Rhode Islanders was the state’s “boy” governor, William Sprague IV (1830-1915), the impetuous and fabulously wealthy heir to a textile manufacturing fortune who had been elected governor at the age of 29. Sprague, who like many northerners presumed the war would end quickly, enthusiastically joined his state’s troops on their excellent adventure (as did several of the men’s female relatives, who “utterly refused to be left at home,” according to The Evening Star). Pulitzer Prize winning author Margaret Leech, in her magisterial Reveille in Washington 1860-1865, says Sprague paraded with his troops wearing military dress and a yellow-plumed hat.2

It was virtually pre-ordained that Sprague and Kate Chase would get together. Margaret Leech notes that she “appeared to be acting in the capacity of hostess at the Rhode Island quarters” and continued to visit when they moved to a hillside encampment in northeast DC. Kate found the rich young governor dashing and exciting. The newspapers’ gossip columns soon were publishing rumors of Kate’s engagement to Sprague, and she would, in fact, marry him two years later in one of Washington’s most celebrated and elaborate fetes.

Kate’s engagement ring, from Tiffany’s in New York, reportedly cost $1,000 (approximately $25,000 today). Sprague showered her with additional wedding gifts said to “exceed those of any of modern date” and be worth nearly $100,000 (about $2.5 million).3 Six hundred of the country’s most important people were invited to the elaborate wedding at the the 6th Street house. The Marine Band was present, playing the romantic “Kate Chase March” when the bride appeared.4 Abraham Lincoln attended the reception, but Mary Todd Lincoln did not; she despised the Chases, particularly Kate, who effortlessly usurped her as the queen of Washington society.

The November marriage began to fray almost immediately. Sprague was away on business for Christmas and New Year’s, starting a pattern that would persist for years. He wrote Kate fawning but bizarre letters, one even asking her permission to have affairs with other women. These he certainly did. One longtime consort even published a novel that was a thinly fictionalized account of her affair with Sprague.5

Meanwhile, Salmon Chase’s political friction with the President never abated, and eventually he resigned from Lincoln’s cabinet. Lincoln, ever tolerant, appointed him Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, perhaps to put him at a remove from politics. In 1869, Chase moved out of the 6th Street house and settled on a 40-acre country estate called Metropolis View that he purchased in upper northeast DC. He renamed it Edgewood and lived there until his death four years later.

The 1870s were hard on Kate and William Sprague. The impulsive William overextended his company financially, and when the Panic of 1873 hit (just after Salmon P. Chase’s death), the company went into receivership, drastically reducing the Spragues’ wealth. Alienated from her erratic husband, Kate openly took up with powerful New York Senator Roscoe Conkling, sparking widespread gossip that they were having an affair. A dramatic incident in 1879 when Sprague discovered Conkling staying with his wife at their Rhode Island estate ultimately led to the undoing of all three. Kate sued for and obtained a divorce from Sprague in 1882, demanding to be allowed to resume her maiden name. Penniless and shunned by high society, Kate lived out her later years in quiet dignity at the Edgewood estate. Read more about Kate and Edgewood in Robert Malesky’s excellent essay on the Bygone Brookland blog.

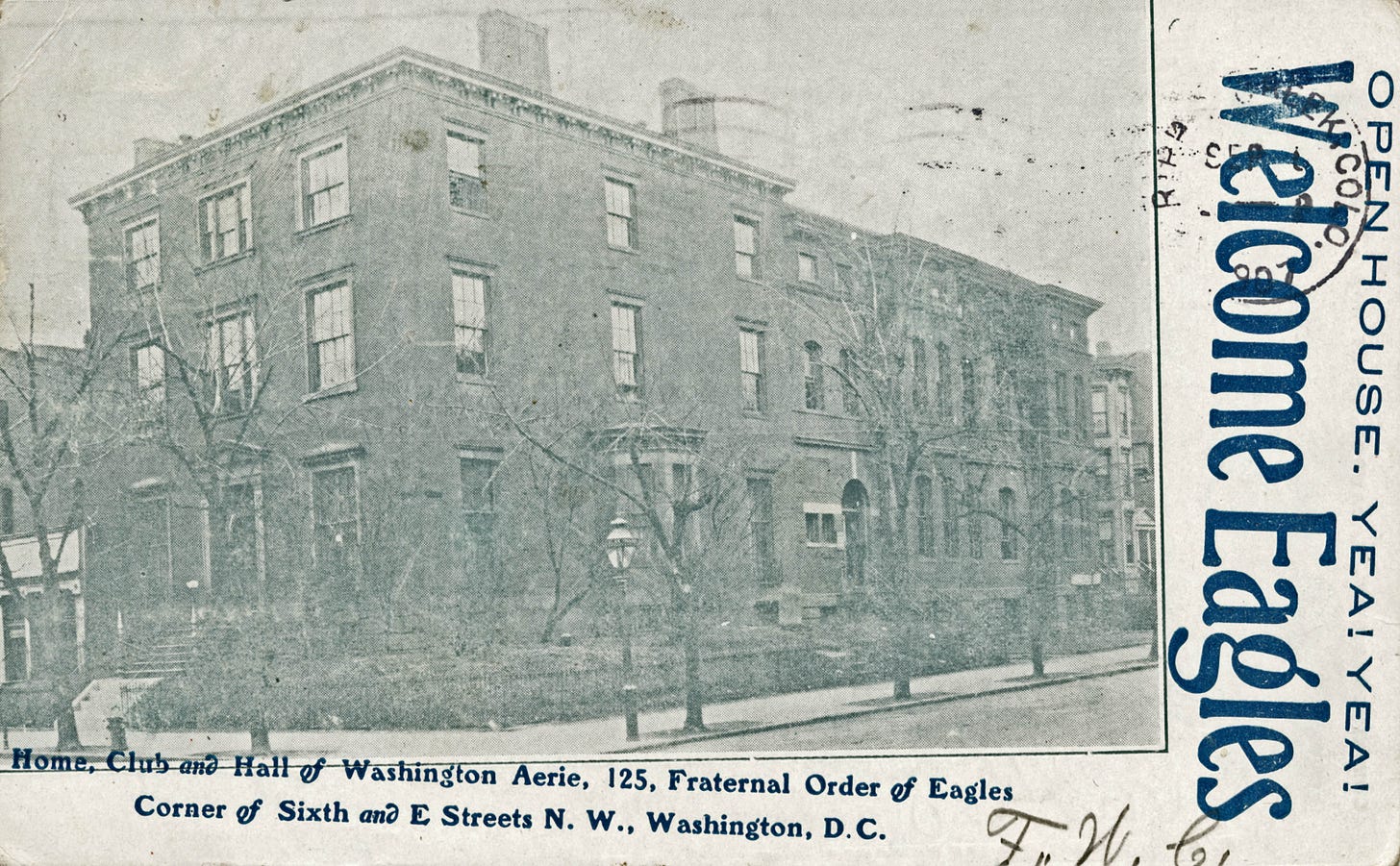

The house at 6th and E streets became a boardinghouse in the late 19th century, when a large wing was added at the rear. Around 1907, it was acquired by the Fraternal Order of Eagles, a fast-growing benevolent society that had been founded in Seattle in 1898. The Eagles’ aim was to “make human life more desirable by lessening its ills and promoting peace, prosperity, gladness and hope.” Dubbed “Eagle Hall,” the clubhouse remained in the hands of the local “aerie” through the 1910s. At one point, a large sculpture of an eagle perched on the front lawn (see circa 1918 photo above).

The Eagles left the house by 1920, when it became the National Catholic Community House, a boardinghouse run by the Catholic Daughters of America.

In the 1930s, the Hecht Company, whose sprawling department store took up much of the other side of the block, sorely needed space for customer parking. The company bought the old Chase mansion, demolished it in 1936, and built a new parking garage in its place.6

The Hecht Company left the neighborhood in 1985, opening the southeastern part of the block to redevelopment. the American Association of Retired Persons took the opportunity to building a large new headquarters building on the site. Designed by Arthur May and completed in 1991, the AARP building now completely overwhelms its historic downtown corner, giving no hint of the intimate scale of buildings that were once there or their tale of social triumph and tragedy.

John Oller, American Queen: The Rise and Fall of Kate Chase Sprague, Civil War “Belle of the North” and Gilded Age Woman of Scandal, (Da Capo Press, 2014), xvii.

Margaret Leech, Reveille in Washington 1860-1865, (Harper & Brothers, 1941), 68-9.

“Miss Chase’s Betrothal Ring,” Daily National Republican, Jul. 28, 1863, 2; “The Wedding of Miss Chase,” Evening Star, Nov. 12, 1863, 3.

“Wedding March,” Daily Morning Chronicle, Nov. 13, 1863,

Oller, 50-1.

James M. Goode, Capital Losses, 2nd ed., (Smithsonian Books, 2003), 60-1.

As always, love this site. Well-researched local history, intriguing subject matter, written with flair.

Thank you for a great article. I have been intrigued with Kate Chase for years. At 21 and as a young woman, she was a major player in US politics and DC society and considered one of if not the most eligible woman in the Country. She married Sprague who was, I believe, the richest man in the Country at the time. By the end, she had lost most everything and was somewhat shunned due to her affair with Conklin. Unfortunately she did not die with quite so much elegance as you describe as she was selling vegetables and eggs door to door to try to stay alive while the family estate was falling apart around her. The wealth that she had while married to Sprague was extreme, and her spending at that time was extreme as well. It is sad as in todays world, she would have been a political star and her death an internationally recognized event. Her father was quite accomplished but an ass. He was forever and surreptitiously trying to assume the presidency (often with Kates assistance) from Lincoln and also forever resigning his cabinet position with the expectation that Lincoln would refuse his resignation. Finally Lincoln had enough and accepted.