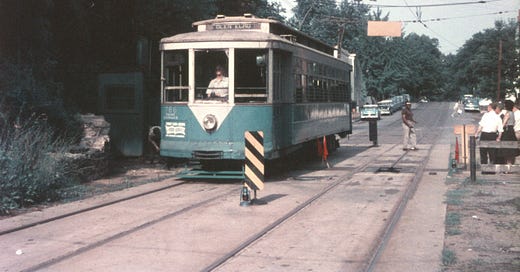

Streetcar at a "plow pit" in Georgetown, late 1950s

It's how they switched between underground and overhead power sources

On a warm day sometime in the late 1950s, a streetcar fan snapped this photo at 37th and Prospect Streets NW at the western edge of Georgetown. He was undoubtedly excited to document the presence of this vintage 1918 streetcar, which by the 1950s was only used for special fan trips. At quick glance, it seems like the streetcar is stopping momentarily at some kind of crosswalk. But a closer look reveals the true story.

The streetcar has stopped over a plow pit, a small underground chamber just beneath the tracks. “Pitmen” were stationed at these small enclosures, which were located at a handful of sites around the city where underground conduits ended and overhead trolley lines began. Note the little sentry box in the shadows, where the pitman could wait when no streetcars were coming. When a streetcar arrived, it was his job to get down in the plow pit and, once the streetcar rolled to a stop overhead, either attach or detach a special forked pole with electrical contacts known as a “plow” to or from the underside of the car. Meanwhile, another worker (a conductor in the days when streetcars had them) would either extend the car’s trolley pole up to the overhead wire or fold it down and stow it on the roof of the car. Once these tasks were completed, a bell would be rung to signal the driver to continue on his way. In experienced hands, this all took less than a minute.

The scene in the photo is facing east, toward Georgetown, and if you look closely, you can see that the slot in the middle of the tracks for the electrical plow starts in the middle of the righthand tracks and continues in the distance. The tracks in the foreground have no central slot. Also, there aren’t any overhead wires in the distance toward Georgetown; they start here and continue behind the photographer toward Glen Echo.

The District’s complicated system for powering streetcars began in the late 1880s, when electric power was first introduced. In 1888 a streetcar line called the Eckington & Soldiers Home Railway opened, connecting the new community of Eckington with downtown. It was the city’s first electric trolley line—the word “trolley” referring to a streetcar that gathers electric power from overhead lines through a pole on the roof of the car. For many Washingtonians, the revolutionary Eckington trolley was a marvel to behold, but for other observers, notably Crosby S. Noyes, editor of The Evening Star, it was a horror. Under Noyes’ editorial leadership, the Star had been waging an aggressive campaign against the use of overhead wires for the distribution of electricity to downtown buildings. The Star argued the wires were unsightly, posed a danger of electrocution, would interfere with the operations of the fire department, and would be impossible to eradicate at a later date if ever allowed to gain a foothold. The proliferation of hundreds of tall wooden poles strung with colossal nests of wires was an evil that, in the view of Noyes and others, had to be stopped.

Spurred to action, Congress in 1889 passed legislation requiring D.C. streetcar lines to convert to electric power using systems that did not require overhead wires. This restriction applied roughly to the limits of the original L’Enfant-designed city—the portion of the District south of Florida Avenue, plus Georgetown. After exploring other options such as batteries and steam-powered cables, DC streetcar companies adopted a system of underground trenches carrying electrified rails that delivered power to streetcars through “plows.” It was very expensive to install and maintain this system, so none of the companies used it anywhere beyond where it was required. Hence the need for facilities—plow pits—where cars could convert between underground and overhead power.

If you’re thinking the plow pit procedure must have been complicated and dangerous, well, you’re right. It was fraught with danger, especially in the early 1900s, when worker safety was not a top priority. The pitmen worked in close proximity to the electrified third rail as well as numerous other live wires: “Thousands of volts of electricity are chained in those wires which crawl about on every side of the cave [plow pit]. Let a single loose installation occur or a wire be snapped in a storm, and the pit would be instantly charged with a voltage equal to that of the death chair in Sing Sing,” The Washington Times ominously noted in 1904.1

The pitmen were supposed to flip switches to turn the current off when they attached or detached the plow. Electrocutions could occur if the switches weren’t set properly. Sadly, in July 1901, a pitman named James Looney was electrocuted here at the Prospect Street plow pit. Looney, 32 years old with a wife and two small children, regularly worked at another pit on 7th Street NW, but he was at the Prospect Street pit that day to make some extra money. Apparently, the power was not cut off as it should have been. Looney received a lethal shock when he accidentally backed up against an electrified metal rod He was rushed to Georgetown University Hospital, only two blocks away, but died within minutes of arriving.2

In those days, electrocution wasn’t the only hazard. In a few cases, a more gruesome end came to pitmen who happened to poke their heads up out of the pit at the wrong moment. Such was the case with Edward Cosack, who was working the Anacostia pit one day in January 1902. He had just attached a plow to a southbound car headed over the Navy Yard bridge into the city when he moved over to the adjacent pit on the northbound side of the tracks and looked up to see what was going on, thinking that side was clear. A northbound car was arriving at that very instant. “The car struck him, crushing his skull and lacerating his face and scalp in a frightful manner,” The Washington Post reported. He was killed instantly.3

Pitmen might attach and detach plows hundreds of times in a shift. For this they earned about two dollars a day in the early 1900s. The job was hard and lonely, but pitmen made the most of their isolated outposts. The accommodations at the Eckington plow pit reportedly included a potbellied stove for heat in the winter as well as a bench, books, magazines, a checkerboard, and pictures taped to the walls. When traffic was busy, some pitmen might stay down in their pits for most or all of their shifts. On lighter routes, they would come out and wait by the side of the road or in shacks like the one on Prospect Street. Passengers on arriving cars were often fascinated to watch the pitmen scurry out into the middle of the street and disappear in the hole just before the car rode over them. —A slice of long-ago life in Washington, DC.

Portions of this article were adapted from the author’s Capital Streetcars: Early Mass Transit in Washington, D.C. (History Press, 2015). Special thanks to the staff of the National Capital Trolley Museum for all their help in researching that book.

“Man in the Electric Pit—Washington’s Oddest Occupation,” Washington Times, Apr. 10, 1904.

“Caused By Electricity,” Evening Star, Jul. 29, 1901, 7; “Fatally Hurt in Plow Pit,” Washington Times, Jul. 29, 1901, 8.

“Met Death in a Plow Pit,” Washington Post, Jan. 25, 1902, 3.

As a child, I loved the streetcar ride to Glen Echo. That was on the Cabin John line, a name that mystified me because my Mom who accompanied me had no interest in going past Glen Echo and I visualized a rustic log cabin named John. I never did make it to Cabin John.

Fascinating Story. Thanks!