The Hecht Company, last of DC's department stores

When Hecht's finally ceased to exist in 2006, it was more than just the end of one of Washington's oldest and most successful businesses. It was the end of large-scale, locally-owned retail as an industry. Other local department store giants, some of which we have previously chronicled, had already fallen: Lansburgh's in 1972, Kann's in 1975; Garfinkel's in 1990; and Woodies in 1995. For a long time, Hecht's bucked this trend. When the company built a brand-new, freestanding store downtown in 1985, it seemed to breathe new life into a tired enterprise and bolster the resurgence of downtown as a shopping destination. But nothing lasts forever.

Hecht's was not a native Washington company; it began in Baltimore after the arrival in 1844 of Simeon Hecht, a native of the small Bavarian town of Langenschwarz. Simeon began the first of several Hecht family enterprises when he opened Hecht's Red Post Store in Baltimore in 1848. His financial success allowed him to bring other family members over to America, including his brother Samuel (1830-1907), who arrived in 1847 and opened a separate furniture business. It was Samuel's son Moses (1873-1954) who set his sights on Washington, opening his "dream store" at 515 7th Street NW in 1896.

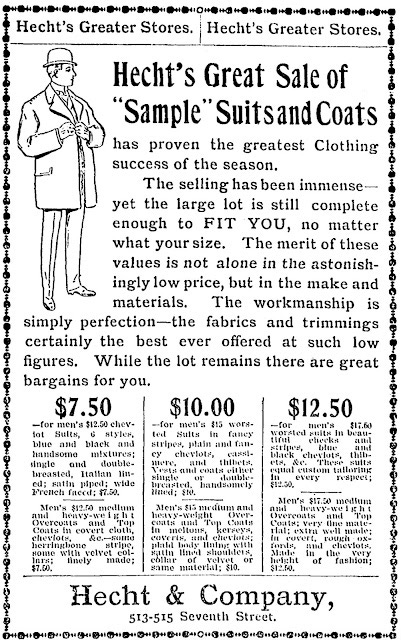

This was the golden era of department stores, prime inventors of modern consumer culture. Offering a vast assortment of stylish goods to make modern life comfortable proved enormously profitable, and the new Hecht's enterprise faced competition from several established D.C. firms. Lansburgh's had been around since 1860 and was located just a block south of Hecht's on 7th Street. On Pennsylvania Avenue, the Palais Royal started in 1877, followed by Woodies (as the Boston Dry Goods Store) in 1880. Kann's had opened as a low-cost alternative in 1893.

Despite this competition, Hecht's thrived. A notice in The Washington Post in 1897 claimed that the store's fall opening gala that year drew a remarkable 10,000 patrons. The following year, the store took over the adjoining building at 513 7th Street, doubling its floor space. A second, six-story addition was built at 517 7th Street in 1903, further expanding the store. Twenty new departments filled the space, including a large furniture department on the top floor. In 1912, Hecht's tacked on another addition, four stories tall, at 511 7th Street.

That Hecht's customers could make their purchases on credit (not just by paying in installments) was touted in the newspapers as key to the store's early success. "It is one of Washington's best-known business houses," the Post proclaimed in 1908, "catering to a large and important portion of the citizenship...the highest official and the daily wage worker sharing the advantages made possible by the unique system of 'buy now—pay later' that has become so famous." Special discreetly-enclosed booths for applying for credit were installed, "into which the customer enters, is waited on by a bookkeeper, and passes out unobserved by the shoppers," according to a 1903 Post article. Once approved, delighted customers snapped up the fancy goods displayed in the gleaming plate-glass and mahogany cases.

As historian Richard Longstreth has explained, the department store business surged after World War I. With the sacrifices of the war over and the economy booming, consumers began spending money on items they had never know they needed. Department stores expanded to meet the growing demand and implemented modern managerial efficiencies to streamline their massive operations and offer even better prices.

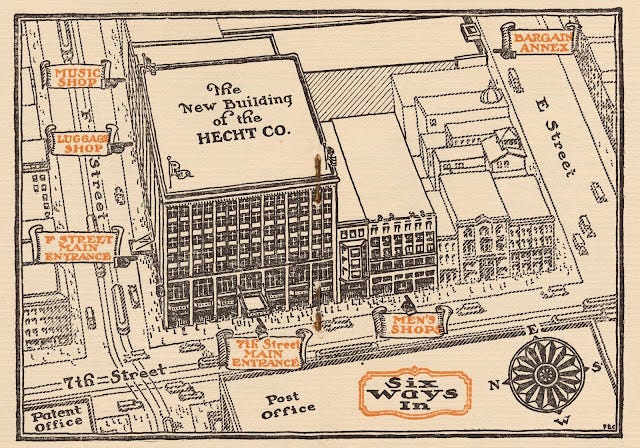

In 1919, Hecht's purchased the Federal Building at the corner of 7th and F, adjacent to its existing store, as well as the Shubert-Garrick Theater adjoining it on F Street, to make room for a large new addition. The theater and the Federal Building's tenants were allowed to run out their leases; then both structures were demolished. In July 1924, groundbreaking took place for a lavish new building, completed the following year. Designed by Chicago architect Jarvis Hunt (1859-1941), the new eight-story store was a forceful statement of the company's success and future aspirations. The glazed terracotta façade, intricate ironwork decoration, and large clock over the intersection of 7th and F Streets, created in a style called "American Gothic" at the time, contributed to the "new conception of shopping convenience and beauty" that the company conveyed. The $3 million building tripled the store's floor space and led to a doubling of its staff, from around 500 to more than 1,000 employees.

Hecht's boasted that enough electricity for a small town was used to power all the lights and equipment in the new store. The massive plate glass windows at street level, like those at other department stores, enticed customers with fetching and often whimsical displays of the latest fashions and household gadgets.

Hecht's never managed to gain the prestige of Woodies or Garfinkel's, but aimed squarely to satisfy the common man. As a 1925 advertisement explained, the store's ambition was "to be one of your best stores. Not your most exclusive store, or your most expensive store, or your ritziest store, but simply one of your best stores—to take our place in the sun with the other splendid department stores in Washington." When Woodies put elaborate displays in its windows at Christmastime, Hecht's didn't try to compete. "Woodies was solid middle class, with an air of gentility but no arrogance. Hecht's was blue collar," wrote Post reporter Roxanne Roberts in 1995, when Woodies closed.

One problem for a multi-story retail establishment like Hecht's was moving customers from one floor to another. Elevators were slow and cumbersome. The answer was escalators. In 1934, Hecht's installed the city's first escalators in its 7th Street store. It held an elaborate dedication ceremony in September, with the chairman of the Depression-era Reconstruction Finance Corporation on hand to cut the ribbon and take the first ride, implicitly assuring onlookers that Hecht's modern escalators were an emblem of better times ahead.

The company continued to add to its department store complex, endlessly fighting to match or outdo its competitors. The company gradually took over most of the block where the main store was located. In December 1935, Hecht's purchased the historic home of Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase (1808-1873) at 6th and E Streets NW on the far side of the block. The handsome Greek Revival mansion, built in 1851, had hosted many an elegant fete during the Civil War years, but Hecht's had no interest in preserving such history. The company wanted the site for automobile parking—a crucial amenity needed to keep customers coming downtown. The Chase house was torn down and replaced initially with a parking lot. In 1937, a modern, utilitarian parking garage was constructed on the site. Hecht's was the first downtown department store to build such a garage. This was followed in 1941 by a new six-story annex on E Street to house Hecht's "bargain store."

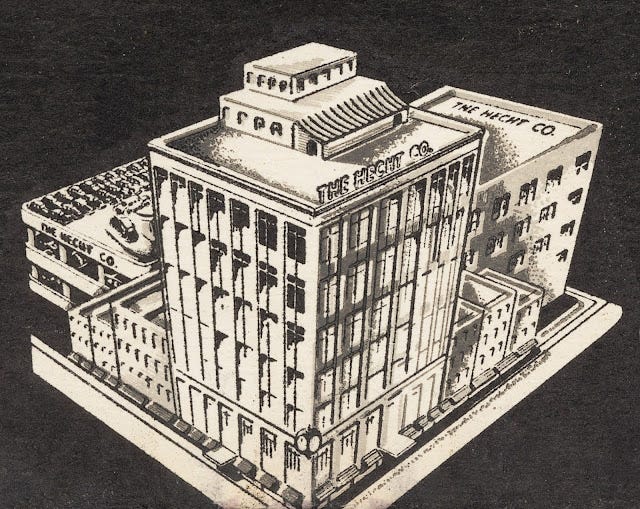

As it expanded, Hecht's, like Woodies, sought to transfer much of its service operations outside of the downtown area. The solution was a new, beautifully-streamlined Art Deco warehouse along New York Avenue NE in Ivy City, which opened in 1937. The building remains one of the city's finest examples of Art Deco styling. The Washington Herald noted that the building was "symbolic of an arresting type of architecture that is destined to precipitate a revolutionary transformation in the appearance and utility of the buildings..." Expanded several times, the structure was used by Hecht's as a warehouse until 2006. It was converted to apartments in 2015.

After World War II, it became clear that branch stores would be essential for any department store that wanted to thrive in the automobile age. A huge base of customers lived in the suburbs, and fewer and fewer of them wanted to come downtown to do their shopping. In 1947, Hecht's opened its first full-service suburban branch in a hulking structure at the corner of Fenton Street and Ellsworth Drive in Silver Spring, Maryland (now part of the Ellsworth Place shopping center). By the 1960s, suburban stores had redefined the retail business. Hecht's opened some 20 more outlets in the Baltimore/Washington area between 1947 and 2005.

As suburban shopping expanded, downtown business withered. Hecht's location in the "old" part of downtown, which declined precipitously after the 1968 riots, became a liability. By 1980, the company was losing as much as $1 million per year on the downtown store, and company officials began searching for a better location. Partnering with developers Oliver Carr and Theodore Hagans, the company decided to build a new store on a site adjacent to the Metro Center subway stop, where downtown redevelopment was beginning to take hold. The proposed site, owned by the city's Redevelopment Land Agency, was on G Street between 12th and 13th Streets, within a few blocks of the Woodies and Garfinkel's stores.

Construction on the block-long store began in 1984. Seven small businesses were evicted from their vintage storefront buildings, which were razed. The vast, new Hecht's structure, the first new department store downtown since before World War II, rose in their place and opened in 1985. Designed by the firm of Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill, the postmodern structure was solidly sheathed in precast concrete, trimmed with pink granite. Like many a suburban department store, the Hecht's building lacked windows, focusing shoppers' experience on the interior displays. At a height of five stories, it was designed so that office space could be built on top at a later date (the One Metro Center offices were added in 2003).

Hecht's sought to win over affluent shoppers with the new store's luxurious marble floors, mahogany paneling, and brass fixtures, which contrasted dramatically with what had become the tired, bargain-basement look of the old building. None of the merchandise from the old store was brought over to the new. No thrift shop or bargain department, in the basement or elsewhere, was to be found. Upscale brands like Anne Klein, Christian Dior, and Ralph Lauren, never seen before in a Hecht's store, graced the new shelves. Prices were substantially higher too, and the strategy worked. Sales increased, and the store became a lasting element of the downtown retail landscape.

But Hecht's, as a brand, is gone. The original, independent Hecht Company had come to an end in 1959, when it merged with the May Department Stores conglomerate. Individual stores had retained the Hecht's brand name but became part of a vast national network of many different labels. In 2006, the May Company merged with Federated Department Stores, which owned the Macy's and Bloomingdale's brands, among others. Wanting to turn Macy's into a national brand, Federated closed some Hecht's stores and rebranded the rest as Macy's (or in one case, Bloomingdale's). Suddenly Hecht's was gone, after 110 years in Washington. Although perhaps not as fondly remembered as Woodies, Hecht's had many followers, and its loss was widely lamented. Post columnist Marc Fisher called it "the last big goodbye in a long series of losses of local retail names."

Macy's remains open in the big box on G Street, still sporting "The Hecht Company" in huge letters chiseled across its façade. In the age of Amazon, who knows how long that store will survive.

Sources for this article included James M. Goode, Capital Losses 2nd ed. (2003); Robert Hendrickson, Grand Emporiums: The Illustrated History of America's Great Department Stores (1981); Michael J. Lisicky, Baltimore's Bygone Department Stores: Many Happy Returns (2012); William Leach, Land of Desire: Merchants, Power, and the Rise of a New American Culture (1993); Richard Longstreth, The American Department Store Transformed 1920-1960 (2010); G. Martin Moeller, Jr., AIA Guide to the Architecture of Washington, D.C. 5th ed. (2012); Jan Whitaker, The World of Department Stores (2011) and Service and Style: How the American Department Store Fashioned the Middle Class (2006); Hanz Wirz and Richard Striner, Washington Deco: Art Deco in the Nation's Capital (1984); Henry F. and Elsie Rathburn Withey, Biographical Dictionary of American Architects (1956); and numerous newspaper articles.