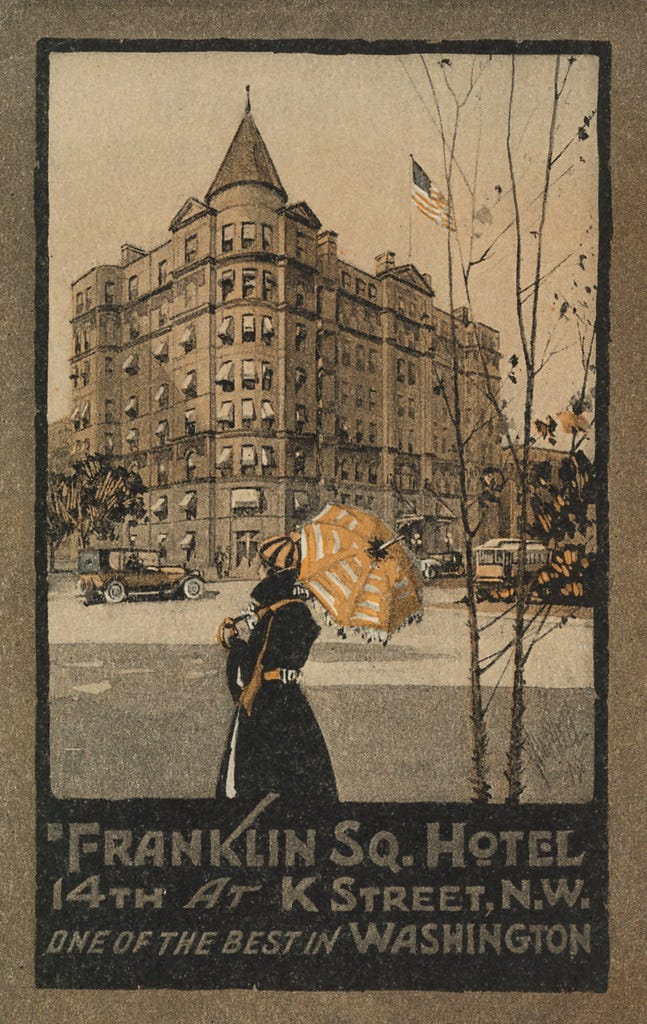

Victorian elegance at the Cochran Hotel, opposite Franklin Square

It was one of three hotels that have stood at this intersection.

Born in Washington in 1824, tobacconist George W. Cochran first opened a cigar store on Pennsylvania Avenue in 1849. It was a great success. Years later, he purchased a fine home for himself and his family on K Street NW near 14th Street. At the time of the Civil War, that neighborhood was one of the most exclusive residential communities in the city. Hugh McCulloch, Secretary of the Treasury under Lincoln and Johnson, owned a handsome mansion at the northwest corner of 14th and K, just two doors down from what would become Cochran’s house.

By the 1890s, Cochran was ready for something new. Seeing a business opportunity, he purchased the old McCulloch mansion as well as the one next to it on K Street (his being third in the row) and tore all of them down to build a fancy new seven-story hotel. Designed by John B. Brady and completed in 1891, the Cochran Hotel, where George Cochran lived, would stand as a notable landmark for many years. The Washington Post, a reliable booster for major real estate developments in those days, offered this detailed description at the time of its opening:

Towering heavenward seven stories at the northwest corner of Fourteenth and K Streets is a model modern structure constructed of Hummelstown brownstone and pressed brick, inscribed Cochran, and designed for the purposes of a first-class hotel....

Stairways connecting the various floors are iron-framed throughout and in the front portion of the house the steps are of white marble, while in the rear portion they are of solid iron, all being graduated so as to furnish an easy ascent. The lobby, where the office is situated, and, in fact, the entire first floor, is tiled with white marble, and a short flight of white stairs leads from the office to the entresol parlor, overlooking Franklin Park, Thomas Circle, and K Street.

From K Street, there is an entrance for ladies, and just upon the right of the main door at this point is a cozy reception room.... Imposing oaken doors are conspicuous in the square entrance on Fourteenth Street into the office, semicircular windows of French plate glass surmounting the doors... Hard wood and tiled mantels are prominent features in the 154 living-rooms, arranged en suite, every other room being provided with a private bath, and sanitary plumbing has been made predominant...

[A]ll the apartments of the Cochran have been elaborately and sumptuously furnished, the carpets being principally moquette, Axminster, and Wilton, while cherry, mahogany, and antique oak predominate in the woods used for the furniture....

Every precaution has been taken against fire and other accidents...in the corridor of each floor is a large fire gong and appliances for extinguishing flames at a moment's notice. Chemicals in small bottles are within easy reach, and long lines of hose are carefully coiled in readiness for instant use....

Cream-tinted tiles, similar to those used in the bathrooms and private apartments of the President's house, abound in the bathrooms of the Cochran, and the side walls are finished in gray Acme cement, similar in appearance to soapstone… For guests who prefer it, provision has been made so that they can have an open grate fire in their apartments, and nothing cozier can be imagine than one of those beautiful nooks in the Cochran, where the tired traveler, in dressing gown and slippers, indeed takes life easy after a long and tedious journey….1

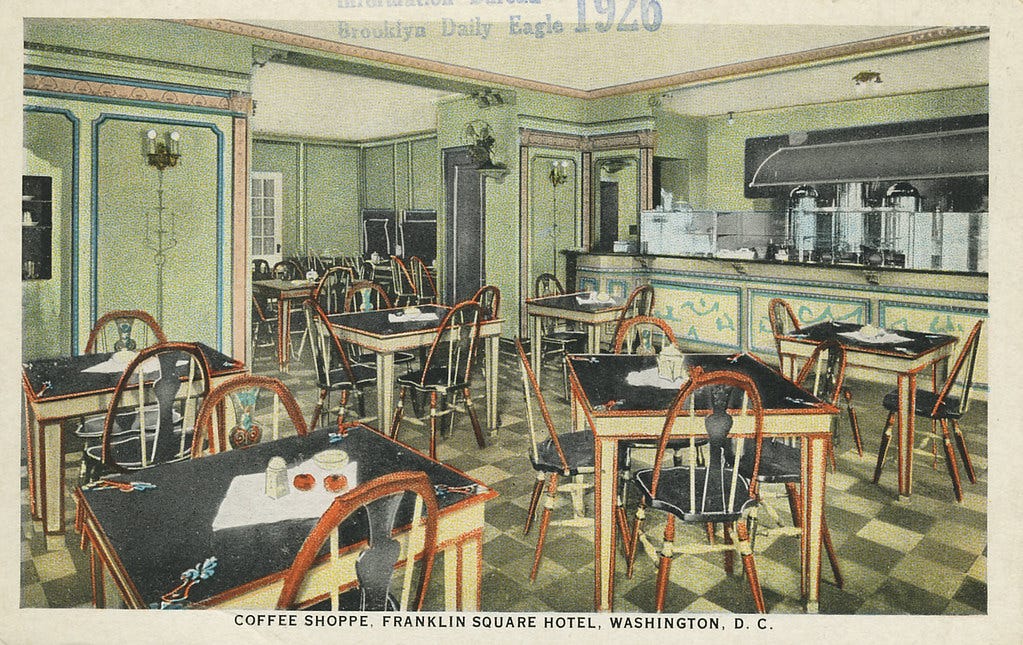

With these glowing words, the hotel was off to a propitious start. It operated as the Cochran Hotel for almost 30 years before former Senator Charles W. F. Dick of Ohio bought and remodeled it as the Franklin Square Hotel in 1920.2 But the renovated hotel never gained traction. A brief newspaper notice in 1921 noted that architect Philip M. Julien was suing the Franklin Square Hotel Company, claiming he hadn’t been fully paid for his remodeling services. The company was further sued in 1926 by its landlord for $62,500 in back rent, and it went into receivership. It soon closed, and the building was razed in 1928.

Perhaps the Franklin Square Hotel was facing too much competition. Directly across 14th Street stood the Hotel Hamilton, which had been operating on the northeast corner since 1877. In 1922, the original Hamilton Hotel had been replaced with a much larger 11-story, 400-room, Beaux-Arts structure, designed by celebrated Washington architect Jules Henri de Sibour. The distinguished hostelry doubtless put the out-of-date Franklin Square Hotel to shame.

As the Cochran sank into bankruptcy and closed, another rival hotel was going up on the southwest corner, directly across K Street. There developer Morris Cafritz built the 500-room Ambassador, a classy Art Deco hostelry, which opened in 1929. The Ambassador was advertised as “the first hotel in Washington equipped with a radio loud speaker in every room and one of the first hostelries in the country in which radio will be part of the customary service without extra charge.”3 The neighborhood had changed dramatically.

In place of the demolished Franklin Square Hotel, a new Art Deco office building, called the Tower Building, was constructed at a cost of $1.2 million. Designed by Robert F. Beresford, it was the tallest office building in the city when it was completed. Unlike the old hotel’s pressed brick and brownstone, the Tower Building was a modern, limestone-clad steel structure, as cutting-edge in the 1920s as the hotel had been in 1891. To conform to new zoning regulations, the building featured a dramatic setback above the 11th floor.

The Tower building opened in June 1929, just four months before the stock market crash that spelled the end of office construction downtown for many more years. Nevertheless, the Tower Building seems to have weathered the economic downturn well. Its elegant double-height first floor commercial space was meant to be used by a bank but instead originally served as a Western Union office. The building was landmarked in 1995 and was subsequently renovated and restored.

An earlier version of this article appeared on Streets of Washington in March 2010.

“Model Modern Hotel,” Washington Post, Nov. 9, 1891, 5.

“Remodeled by New Owner, Renamed Franklin Park,” Washington Herald, Jan. 10, 1920, 3.

“Every Ambassador Room Has Radio Loud Speaker,” Washington Post, Sep. 22, 1929, AS7.

Great learning of the history of this block and the current Tower Building.

I spent many a night at the DC Coast bar which was the restaurant there from late 90s through the 2010s.

The Ambassador Hotel also eventually had a large basement indoor pool that at least by the sixties could be visited by non-hotel guests as I often did as a young teenager.